Encyclopedia of British Football

~ Football Rules ~

|

In the 18th century football

was played by most of Britain's leading public schools. There is

documentary evidence that football was played at Eton as early as 1747.

Westminster started two years later. Harrow, Shrewsbury, Winchester and

Charterhouse had all taken up football by the 1750s.

Thomas Arnold was appointed headmaster of Rugby in 1828. He had a

profound and lasting effect on the development of public school

education in England. Arnold introduced mathematics, modern history and

modern languages and instituted the form system and introduced the

prefect system to keep discipline. He modernized the teaching of

Classics by directing attention to literary, moral or historical

questions. Although Arnold held strong views, he made it clear to his

students they were not expected to accept those views, but to examine

the evidence and to think for themselves.

Arnold also emphasized the importance of sport in young men's education.

Like most head teachers in public schools, Arnold believed that sport

was a good method for "encouraging senior boys to exercise responsible

authority on behalf of the staff". He also argued that games like

football provided a "formidable vehicle for character building".

Each school had its own set of rules and style of game. In some schools

the ball could be caught, if kicked below the hand or knee. If the ball

was caught near the opposing goal, the catcher had the opportunity of

scoring, by carrying it through the goal in three standing jumps.

Rugby, Marlborough and Cheltenham developed games that used both hands

and feet. The football played at Shrewsbury and Winchester placed an

emphasis on kicking and running with the ball (dribbling). School

facilities also influenced the rules of these games. Students at

Charterhouse played football within the cloisters of the old Carthusian

monastery. As space was limited the players depended on dribbling

skills. Whereas schools like Eton and Harrow had such large playing

fields available that they developed a game that involved kicking the

ball long distances.

According to one student at Westminster, the football played at his

school was very rough and involved a great deal of physical violence:

"When running... the enemy tripped, shinned, charged with the shoulder,

got down and sat upon you... in fact did anything short of murder to get

the ball from you."

Football games often led to social disorder. As Dave Russell pointed out

in Football and the English (1997), football had a "habit of bringing

the younger element of the lower orders into public spaces in large

numbers were increasingly seen as inappropriate and, indeed, positively

dangerous in an age of mass political radicalism and subsequent fear for

public order."

Action was taken to stop men playing football in the street. The 1835

Highways Act provided for a fine of 40s for playing "football or any

other game on any part of the said highways, to the annoyance of any

passenger."

In 1840 soldiers had to be used to stop men playing football in

Richmond. Six years later the Riot Act had to be read in Derby and a

troop of cavalry was used to disperse the players. There were also

serious football disturbances in East Molesey, Hampton and

Kingston-upon-Thames.

Although the government disapproved of the working-classes playing

football, it continued to be a popular sport in public schools. In 1848

a meeting took place at Cambridge University to lay down the rules of

football. As Philip Gibbons points out in Association Football in

Victorian England (2001): "The varying rules of the game meant that the

public schools were unable to compete against each other." Teachers

representing Shrewsbury, Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Marlborough and

Westminster, produced what became known as the Cambridge Rules. One

participant explained what happened: "I cleared the tables and provided

pens and paper... Every man brought a copy of his school rules, or knew

them by heart, and our progress in framing new rules was slow."

It was eventually decided that goals would be awarded for balls kicked

between the flag posts (uprights) and under the string (crossbar). All

players were allowed to catch the ball direct from the foot, provided

the catcher kicked it immediately. However, they were forbidden to catch

the ball and run with it. Only the goalkeeper was allowed to hold the

ball. He could also punch it from anywhere in his own half. Goal kicks

and throw-ins took place when the ball went out of play. It was

specified that throw-ins were taken with one hand only. It was also

decided that players in the same team should wear the same colour cap

(red and dark blue).

Sometimes public schools played football against boys from the local

town. Although these games often ended in fights, it did help to spread

knowledge of Cambridge Rules football. Former public school boys also

played football at university. Many continued to play after finishing

their education. Some joined clubs like the Old Etonians, Old Harrovians

and the Wanderers (a side only open to men who had attended the leading

public schools), whereas others formed their own clubs. For example,

former pupils of the Sheffield Collegiate School established the

Sheffield Football Club at Bramall Lane. In 1857 they published their

own set of rules for football. These new rules allowed for more physical

contact than those established in Cambridge. Players were allowed to

push opponents off the ball with their hands. It was also within the

rules to shoulder charge players, with or without the ball. If a

goalkeeper caught the ball, he could be barged over the line.

In 1862 a new set of rules were established at Cambridge University.

These specified 11-a-side, an umpire from each side plus a neutral

referee, goals 12ft across and up to 20ft high. An offside rule was

added. A man could play a ball passed to him from behind, so long as

there were three opponents between him and the goal. It was also decided

that each game should only last one hour and a quarter. The first game

under these rules took place between the Old Etonians and Old Harrovians

in November, 1862.

|

A photograph of the Uppingham team. At that time the team played 15-a-side. |

Some public schools refused to accept the Cambridge Rules. At Uppingham

School in Rutland, the students played with an enormously wide goal. In

1862, one of the teachers at Uppingham, John Charles Thring, published

his own set of rules:

1. A goal is scored whenever the ball is forced through the goal and

under the bar, except it be thrown by hand.

2. Hands may be used only to stop a ball and place it on the ground

before the feet.

3. Kicks must be aimed only at the ball.

4. A player may not kick the ball whilst in the air.

5. No tripping up or heel kicking allowed.

6. Whenever a ball is kicked beyond the side flags, it must be returned

by the player who kicked it, from the spot it passed the flag line, in a

straight line towards the middle of the ground.

7. When a ball is kicked behind the line of goal, it shall be kicked off

from that line by one of the side whose goal it is.

8. No player may stand within six paces of the kicker when he is kicking

off.

9. A player is ‘out of play’ immediately he is in front of the ball and

must return behind the ball as soon as possible. If the ball is kicked

by his own side past a player, he may not touch or kick it, or advance,

until one of the other side has first kicked it, or one of his own side

has been able to kick it on a level with, or in front of him.

10. No charging allowed when a player is ‘out of play’; that is,

immediately the ball is behind him.

Thring published his rules under the title, The Simplest Game. Some

teachers liked this non-violent approach and several schools adopted

Thring's rules.

The Football Association was established in October, 1863. The aim of

the FA was to establish a single unifying code for football. The first

meeting took place at the Freeman's Tavern in London. The clubs

represented at the meeting included Barnes, Blackheath, Perceval House,

Kensington School, the War Office, Crystal Palace, Forest (later known

as the Wanderers), the Crusaders and No Names of Kilburn. Charterhouse

also sent an observer to the meeting.

Ebenezer Cobb Morley was elected as the secretary of the FA. At a

meeting on 24th November, 1863, Morley presented a draft set of 23

rules. These were based on an amalgamation of rules played by public

schools, universities and football clubs. This included provision for

running with the ball in the hands if a catch had been taken "on the

full" or on the first bounce. Players were allowed to "hack the front of

the leg" of the opponent when they were running with the ball. Two of

the proposed rules caused heated debate:

IX. A player shall be entitled to run with the ball towards his

adversaries' goal if he makes a fair catch, or catches the ball on the

first bound; but in case of a fair catch, if he makes his mark (to take

a free kick) he shall not run.

X. If any player shall run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal,

any player on the opposite side shall be at liberty to charge, hold,

trip or hack him, or to wrest the ball from him, but no player shall be

held and hacked at the same time.

Some members objected to these two rules as they considered them to be

"uncivilized". Others believed that charging, hacking and tripping were

important ingredients of the game. One supporter of hacking argued that

without it "you will do away with the courage and pluck of the game, and

it will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen who would beat you

with a week's practice." The main defender of hacking was F. W.

Campbell, the representative from Blackheath, who considered this aspect

of the game was vital in developing "masculine toughness". Campbell

added that "hacking is the true football" and he resigned from the FA

when the vote went against him (13-4). He later helped to form the rival

Rugby Football Union. On 8th December, 1863, the FA published the Laws

of Football.

1. The maximum length of the ground shall be 200 yards, the maximum

breadth shall be 100 yards, the length and breadth shall be marked off

with flags; and the goal shall be defined by two upright posts, eight

yards apart, without any tape or bar across them.

2. A toss for goals shall take place, and the game shall be commenced by

a place kick from the centre of the ground by the side losing the toss

for goals; the other side shall not approach within 10 yards of the ball

until it is kicked off.

3. After a goal is won, the losing side shall be entitled to kick off,

and the two sides shall change goals after each goal is won.

4. A goal shall be won when the ball passes between the goal-posts or

over the space between the goal-posts (at whatever height), not being

thrown, knocked on, or carried.

5. When the ball is in touch, the first player who touches it shall

throw it from the point on the boundary line where it left the ground in

a direction at right angles with the boundary line, and the ball shall

not be in play until it has touched the ground.

6. When a player has kicked the ball, any one of the same side who is

nearer to the opponent's goal line is out of play, and may not touch the

ball himself, nor in any way whatever prevent any other player from

doing so, until he is in play; but no player is out of play when the

ball is kicked off from behind the goal line.

7. In case the ball goes behind the goal line, if a player on the side

to whom the goal belongs first touches the ball, one of his side shall

he entitled to a free kick from the goal line at the point opposite the

place where the ball shall be touched. If a player of the opposite side

first touches the ball, one of his side shall be entitled to a free kick

at the goal only from a point 15 yards outside the goal line, opposite

the place where the ball is touched, the opposing side standing within

their goal line until he has had his kick.

8. If a player makes a fair catch, he shall be entitled to a free kick,

providing he claims it by making a mark with his heel at once; and in

order to take such kick he may go back as far as he pleases, and no

player on the opposite side shall advance beyond his mark until he has

kicked.

9. No player shall run with the ball.

10. Neither tripping nor hacking shall be allowed, and no player shall

use his hands to hold or push his adversary.

11. A player shall not be allowed to throw the ball or pass it to

another with his hands.

12. No player shall be allowed to take the ball from the ground with his

hands under any pretence whatever while it is in play.

13. No player shall be allowed to wear projecting nails, iron plates, or

gutta-percha on the soles or heels of his boots.

In 1866 the offside rule was altered to allow a player to be onside when

three of opposing team are nearer their own goal-line. Three years later

the kick-out rule was altered and goal-kicks were introduced.

In 1871, Charles W. Alcock, the FA Secretary, announced the introduction

of the Football Association Challenge Cup. It was the first knockout

competition of its type in the world. Only 15 clubs took part in the

first staging of the tournament. It included two clubs based in

Scotland, Donington School and Queen's Park. In the 1872 final, the

Wanderers beat the Royal Engineers 1-0 at the Kennington Oval.

The 1870s saw several changes to Football Association rules. In 1870

eleven-a-side games were introduced with the addition of a goalkeeper.

1871 also saw the introduction of umpires and a neutral referee. Both

sides were allowed to appoint an umpire to whom players could appeal to

about incidents that took place on the pitch. However, the FA rule now

stated: "Any point on which the umpires cannot agree shall be decided by

the referee".

In 1872 the FA published an updated set of laws. This made it clear that

"a goal shall be won when the ball passes between the goal posts under

the tape, not being thrown, knocked on, or carried." The new rules

clearly distinguished between goalkeepers and other players: "A player

shall not throw the ball nor pass it to another except in the case of

the goalkeeper, who shall be allowed to use his hands for the protection

of his goal... No player shall carry or knock on the ball; nor shall any

player handle the ball under any pretence whatever."

|

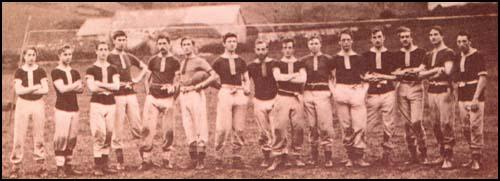

England against Scotland in 1877. Note the lack of crossbars and nets. |

The FA Cup helped to popularize the game of football. Up until this

competition only fifty clubs were members of the Football Association

and played by their rules. This included teams who played as far away as

Lincoln, Oxford and York. The main rival to the FA was the 26-member

Sheffield Association. Other football clubs were totally independent and

played by their own set of rules. In 1877 the clubs in Sheffield decided

to join the FA and by 1881 its membership had risen to 128.

The FA continued to adapt the rules of the game. In 1882 all clubs had

to provide crossbars. Ten years later goal nets became compulsory. This

reduced the number of disputes as to whether the ball had crossed the

goal-line or passed between the posts.

In 1885 it was decided by the Football Association that clubs could play

professionals in the FA Cup competition. It was not long before football

clubs had large wage bills to play. It was therefore necessary to

arrange more matches that could be played in front of large crowds. In

March, 1888 it was suggested that "ten or twelve of the most prominent

clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season."

The following month the Football League was formed. It consisted of six

clubs from Lancashire (Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Burnley, Everton

and Preston North End) and six from the Midlands (Aston Villa, Derby

County, Notts County, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton

Wanders).

In the 1880s football was introduced into most state schools. It could

be played on any hard surface and that was especially attractive to

those schools that did not have access to playing fields. As a high

percentage of the children were physically underdeveloped and

undernourished, soccer was considered to be more suitable than rugby.

The role of the referee changed in 1891. He moved onto the pitch from

the touchline and took complete control of the game. The umpires now

became linesmen. 1891 also saw the introduction of the penalty kick. As

Dave Russell has pointed out in Football and the English (1997) that

this new rule "bitterly upset many amateurs, who argued that the new

legislation assumed that footballers could be capable of cheating."

The shoulder charge remained an important part of the game. This could

be used against players even if they did not have the ball. If a

goalkeeper caught the ball, he could be barged over the line. As a

result, goalkeepers tended to punch the ball a great deal. In 1894 the

Football Association introduced a new law which stated that a goalkeeper

could only be charged when playing the ball or obstructing an opponent.

In September, 1898, the South Essex Gazette reported that in a game

against Brentford, two West Ham United players, George Gresham and Sam

Hay, "bundled the goalkeeper into the net whilst he had the ball in his

hands". The goal stood because this action was within the rules at the

time.

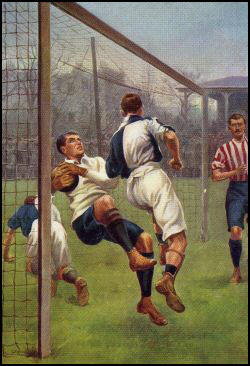

|

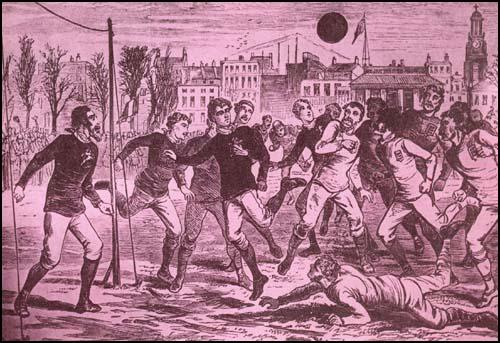

Goalkeeper being legally barged over the goal line in a game in 1904. |

Goalkeepers were allowed to handle, but not carry, the ball anywhere in

their own half of the field. For example, Tommy Moore, who played for

West Ham United, between 1898 to 1901, often moved up field and started

an attack by punching the ball into the opposition half. In a game

against Chesham, the game was so one-sided that Moore spent most of the

game on the offensive. As the local newspaper reported: "Moore had so

little to do that he often left his goal unprotected and played up with

the forwards."

The strategy of using an attacking goalkeeper came to and end in 1912

when the Football Association introduced a new rule that stated that

they could only handle the ball inside the penalty area.

|