|

|

| This Web Site is dedicated to the Memories & Spirit of the Game as only Ken Aston could teach it... |

| Enjoy, your journey here on... KenAston.org |

| Ken Aston Referee Society ~ Football Encyclopedia Bible |

History of Football

|

| Source - References |

| The first description of a

football match in England was written by William FitzStephen in about

1170. He records that while visiting London he noticed that "after

dinner all the youths of the city goes out into the fields for the very

popular game of ball." He points out that every trade had their own

football team. "The elders, the fathers, and the men of wealth come on

horseback to view the contests of their juniors, and in their fashion

sport with the young men; and there seems to be aroused in these elders

a stirring of natural heat by viewing so much activity and by

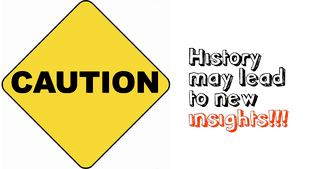

participation in the joys of unrestrained youth." A few centuries later another monk wrote that football was a game "in which young men... propel a huge ball not by throwing it into the air, but by striking and rolling it along the ground, and that not with their hands but with their feet." This chronicler strongly disapproved of the game claiming it was "undignified and worthless" and that it often resulted in "some loss, accident or disadvantage to the players themselves." One manor record, dated 1280, states: "Henry, son of William de Ellington, while playing at ball at Ulkham on Trinity Sunday with David le Ken and many others, ran against David and received an accidental wound from David's knife of which he died on the following Friday." In 1321, William de Spalding, was in trouble with the law over a game of football: "During the game at ball as he kicked the ball, a lay friend of his, also called William, ran against him and wounded himself on a sheath knife carried by the canon, so severely that he died within six days." There are other recorded cases during this period of footballers dying after falling on their daggers. Edward II became involved in the debate on football and in 1314 complained about "certain tumults arising from great footballs in the fields of the public, from which many evils may arise." At the time he was trying to raise an army to fight the Scots and was worried about the impact that football was having on the skills of his archers. |

Longbow men practicing at the butts (Geoffrey Luttrell Psalter, 1325) |

|

In an attempt to make the English the best long bowmen in the world, a

law was passed ordering all men earning less than 100 pence a year to

own a longbow. Every village had to arrange for a space to be set aside

for men to practice using their bows. It was especially important for

boys to take up archery at a young age. It was believed that to obtain

the necessary rhythm of "laying the body into the bow" the body needed

to be young and flexible. It was said that when a young man could hit a

squirrel at 100 paces he was ready to join the king's army. Edward II came to the conclusion that young people were more interested in playing football than practicing archery. His answer to this problem was to ban the playing of the game. His father, Edward III, reintroduced the ban in 1331 in preparation for an invasion of Scotland. Henry IV was the next monarch who tried to stop England's young men from playing football when he issued a new ban in 1388. This was ineffective and in 1410 his government imposed a fine of 20s and six days' imprisonment on those caught playing football. In 1414, his son, Henry V, introduced a further proclamation ordering men to practice archery rather than football. The following year Henry's archers played an important role in the defeat of the French at Agincourt. Edward IV was another strong opponent of football. In 1477 he passed a law that stipulated that "no person shall practice any unlawful games such as dice, quoits, football and such games, but that every strong and able-bodied person shall practice with bow for the reason that the national defense depends upon such bowmen." Henry VII outlawed football in 1496 and his son, Henry VIII, introduced a series of laws against the playing of the game in public places. Whereas the monarchy objected for military reasons, church leaders were more concerned about the game being played on a Sunday. In 1531 the Puritan preacher, Thomas Eliot, argued that football caused "beastly fury and extreme violence". In 1572 the Bishop of Rochester demanded a new campaign to suppress this "evil game". In his book, Anatomy of Abuses (1583) Philip Stubbs argued that "football playing and other devilish pastimes.. with draw thus from godliness, either upon the Sabbath or any other day." Stubbs was also concerned about the injuries that were taking place: "sometimes their necks are broken, sometimes their backs, sometimes their legs, sometimes their arms, sometimes one part is thrust out of joint, sometimes the noses gush out with blood... Football encourages envy and hatred... sometimes fighting, murder and a great loss of blood." However, there were some people who thought that football was good for the health of young men. Richard Mulcaster, the headmaster of Merchant Taylors' School, wrote in 1581, that football had "great helps, both to health and strength." He added the game "strengthened and brawniest the whole body, and by provoking superfluities downward, it discharged the head, and upper parts, it is good for the bowels, and to drive the stone and gravel from both the bladder and kidneys." The records show that young men refused to accept the banning of football. In 1589, Hugh Case and William Shurlock were fined 2s for playing football in St. Werburgh's cemetery during the vicar's sermon. Ten years later a group of men in a village in Essex were fined for playing football on a Sunday. Other prosecutions took place in Richmond, Bedford, Thirsk and Guisborough. Local councils also banned the playing of football. However, young men continued to ignore local by-laws. In 1576 it was recorded in Ruislip that around a hundred people "assembled themselves unlawfully and played a certain unlawful game, called football". In Manchester in 1608 "a company of lewd and disordered persons... broke many men's windows" during an "unlawful" game of football. It was such a major problem that in 1618 the local council appointed special "football officers" to police these laws. After the execution of Charles I in 1649 the new ruler, Oliver Cromwell, instructed his Major-Generals to enforce laws against football, bear-baiting, cock-fighting, horse-racing and wrestling. Cromwell was more successful than previous rulers in stopping young men from playing football. However, after his death in 1660 the game gradually re-emerged in Britain. The ball used in football was made from an inflated animal bladder. Two teams, made up of large numbers of young men, attempted to get the ball into the opposition goal. In towns the game was mainly played by craft apprentices. As James Walvin points out in The People's Game (1994): "Overworked, exploited and generally harboring a range of grievances, they formed a frequently disaffected body of young men, living close to each other... They posed a regular threat of unruliness and not surprisingly, they were readily recruited for football." |

A 17th print showing the inflation of an animal bladder. |

|

According to George Owen (c. 1550) in Wales football was slightly

different from the game played in England: "There is a round ball

prepared... so that a man may hold it in his hand... The ball is made of

wood and boiled in tallow to make it slippery and hard to hold... The

ball is called a knappan, and one of the company hurls it into the

air... He that gets the ball hurls it towards the goal... the knappan is

tossed backwards and forwards... It is a strange sight to see a thousand

or fifteen hundred men chasing after the knappan... The gamesters return

home from this play with broken heads, black faces, bruised bodies and

lame legs... Yet they laugh and joke and tell stories about how they

broke their heads... without grudge or hatred." The gap between the two goals in football games could be several miles. For example, in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, a football game was played annually on Shrove Tuesday. It involved two teams consisting of anyone who lived in the town and the action took place between goals three miles apart. In 1772 a game in Hitchen resulted in the ball being "drowned for a time in the Priory pond, then forced along Angel Street across the Market Place into the Artichoke beer-house, and finally goaled in the porch of St Mary's Church". Large football games often took place on Shrove Tuesday. In 1796 it was reported that in Derby, John Snape was "an unfortunate victim to this custom... which is disgraceful to humanity and civilization, subversive of good order and government and destructive to the morals, properties, and lives of our inhabitants." In the 18th century football was played by most of Britain's leading public schools. There is documentary evidence that football was played at Eton as early as 1747. Westminster started two years later. Harrow, Shrewsbury, Winchester and Charterhouse had all taken up football by the 1750s. In 1801 Joseph Strutt described the game of football in his book, The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England: "When a match at football is made, two parties, each containing an equal number of competitors, take the field, and stand between two goals, placed at the distance of eighty or an hundred yards the one from the other. The goal is usually made with two sticks driven into the ground, about two or three feet apart. The ball, which is commonly made of a blown bladder, and cased with leather, is delivered in the midst of the ground, and the object of each party is to drive it through the goal of their antagonists, which being achieved the game is won. The abilities of the performers are best displayed in attacking and defending the goals; and hence the pastime was more frequently called a goal at football than a game at football. When the exercise becomes exceeding violent, the players kick each other's shins without the least ceremony, and some of them are overthrown at the hazard of their limbs." |

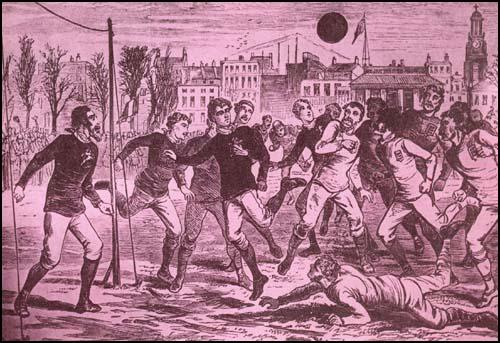

An early game of football. |

|

Thomas Arnold was appointed headmaster of Rugby in 1828. He had a

profound and lasting effect on the development of public school

education in England. Arnold introduced mathematics, modern history and

modern languages and instituted the form system and introduced the

prefect system to keep discipline. He modernized the teaching of

Classics by directing attention to literary, moral or historical

questions. Although Arnold held strong views, he made it clear to his

students they were not expected to accept those views, but to examine

the evidence and to think for themselves. Arnold also emphasized the importance of sport in young men's education. Like most head teachers in public schools, Arnold believed that sport was a good method for "encouraging senior boys to exercise responsible authority on behalf of the staff". He also argued that games like football provided a "formidable vehicle for character building". Each school had its own set of rules and style of game. In some schools the ball could be caught, if kicked below the hand or knee. If the ball was caught near the opposing goal, the catcher had the opportunity of scoring, by carrying it through the goal in three standing jumps. |

Illustration of a public schools game of football in the 1860s. |

|

Rugby, Marlborough and Cheltenham developed games that used both hands

and feet. The football played at Shrewsbury and Winchester placed an

emphasis on kicking and running with the ball (dribbling). School

facilities also influenced the rules of these games. Students at

Charterhouse played football within the cloisters of the old Carthusian

monastery. As space was limited the players depended on dribbling

skills. Whereas schools like Eton and Harrow had such large playing

fields available that they developed a game that involved kicking the

ball long distances. According to one student at Westminster, the football played at his school was very rough and involved a great deal of physical violence: "When running... the enemy tripped, shinned, charged with the shoulder, got down and sat upon you... in fact did anything short of murder to get the ball from you." Football games often led to social disorder. As Dave Russell pointed out in Football and the English (1997), football had a "habit of bringing the younger element of the lower orders into public spaces in large numbers were increasingly seen as inappropriate and, indeed, positively dangerous in an age of mass political radicalism and subsequent fear for public order." Action was taken to stop men playing football in the street. The 1835 Highways Act provided for a fine of 40s for playing "football or any other game on any part of the said highways, to the annoyance of any passenger." In 1840 soldiers had to be used to stop men playing football in Richmond. Six years later the Riot Act had to be read in Derby and a troop of cavalry was used to disperse the players. There were also serious football disturbances in East Molesey, Hampton and Kingston-upon-Thames. Although the government disapproved of the working-classes playing football, it continued to be a popular sport in public schools. In 1848 a meeting took place at Cambridge University to lay down the rules of football. As Philip Gibbons points out in Association Football in Victorian England (2001): "The varying rules of the game meant that the public schools were unable to compete against each other." Teachers representing Shrewsbury, Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Marlborough and Westminster, produced what became known as the Cambridge Rules. One participant explained what happened: "I cleared the tables and provided pens and paper... Every man brought a copy of his school rules, or knew them by heart, and our progress in framing new rules was slow." It was eventually decided that goals would be awarded for balls kicked between the flag posts (uprights) and under the string (crossbar). All players were allowed to catch the ball direct from the foot, provided the catcher kicked it immediately. However, they were forbidden to catch the ball and run with it. Only the goalkeeper was allowed to hold the ball. He could also punch it from anywhere in his own half. Goal kicks and throw-ins took place when the ball went out of play. It was specified that throw-ins were taken with one hand only. It was also decided that players in the same team should wear the same color cap (red and dark blue). Sometimes public schools played football against boys from the local town. Although these games often ended in fights, it did help to spread knowledge of Cambridge Rules football. Former public school boys also played football at university. Many continued to play after finishing their education. Some joined clubs like the Old Etonians, Old Harrovians and the Wanderers (a side only open to men who had attended the leading public schools), whereas others formed their own clubs. Football was a very popular sport in Sheffield and in 1857 a group of men established the Sheffield Football Club at Bramall Lane. It is believed to be the first football club in the world. Two former Harrow students, Nathaniel Creswick and William Prest, published their own set of rules for football. These new rules allowed for more physical contact than those established by some of the public schools. Players were allowed to push opponents off the ball with their hands. It was also within the rules to shoulder charge players, with or without the ball. If a goalkeeper caught the ball, he could be barged over the line. At first the Sheffield Club played friendly games against teams in London and Nottingham. On 29th December, 1862, Sheffield played Hallam in a football charity game. It was one of the first-ever football games to be recorded in a newspaper. The Sheffield Independent reported: "At one time it appeared that the match would be turned into a general fight. Major Creswick had got the ball away and was struggling against great odds - Mr Shaw and Mr Waterfall (of Hallam). Major Creswick was held by Waterfall and in the struggle Waterfall was accidentally hit by the Major. All parties agreed that the hit was accidental. Waterfall, however, ran at the Major in the most irritable manner, and struck him several times. He also threw off his waistcoat and began to show fight in earnest. Major Creswick, who preserved his temper admirably, did not return a single blow." The following week a letter appeared in The Sheffield Independent defending the actions of William Waterfall: "The unfair report in your paper of the... football match played on the Bramall Lane ground between the Sheffield and Hallam Football Clubs calls for a hearing from the other side. We have nothing to say about the result - there was no score - but to defend the character and behavior of our respected player, Mr William Waterfall, by detailing the facts as they occurred between him and Major Creswick. In the early part of the game, Waterfall charged the Major, on which the Major threatened to strike him if he did so again. Later in the game, when all the players were waiting a decision of the umpires, the Major, very unfairly, took the ball from the hands of one of our players and commenced kicking it towards their goal. He was met by Waterfall who charged him and the Major struck Waterfall on the face, which Waterfall immediately returned." In 1862 a new set of rules were established at Cambridge University. These specified 11-a-side, an umpire from each side plus a neutral referee, goals 12ft across and up to 20ft high. An offside rule was added. A man could play a ball passed to him from behind, so long as there were three opponents between him and the goal. It was also decided that each game should only last one hour and a quarter. The first game under these rules took place between the Old Etonians and Old Harrovians in November, 1862. |

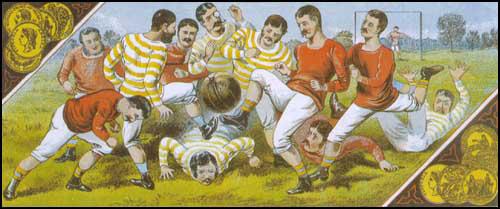

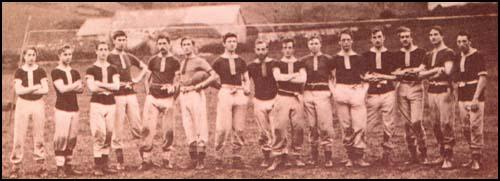

A photograph of the Uppingham team. At that time the team played 15-a-side. |

|

Some public schools refused to accept the Cambridge Rules. At Uppingham

School in Rutland, the students played with an enormously wide goal. In

1862, one of the teachers at Uppingham, John Charles Thring, published

his own set of rules: 1. A goal is scored whenever the ball is forced through the goal and under the bar, except it be thrown by hand. 2. Hands may be used only to stop a ball and place it on the ground before the feet. 3. Kicks must be aimed only at the ball. 4. A player may not kick the ball whilst in the air. 5. No tripping up or heel kicking allowed. 6. Whenever a ball is kicked beyond the side flags, it must be returned by the player who kicked it, from the spot it passed the flag line, in a straight line towards the middle of the ground. 7. When a ball is kicked behind the line of goal, it shall be kicked off from that line by one of the side whose goal it is. 8. No player may stand within six paces of the kicker when he is kicking off. 9. A player is ‘out of play’ immediately he is in front of the ball and must return behind the ball as soon as possible. If the ball is kicked by his own side past a player, he may not touch or kick it, or advance, until one of the other side has first kicked it, or one of his own side has been able to kick it on a level with, or in front of him. 10. No charging allowed when a player is ‘out of play’; that is, immediately the ball is behind him. Thring published his rules under the title, The Simplest Game. Some teachers liked this non-violent approach and several schools adopted Thring's rules. The Football Association was established in October, 1863. The aim of the FA was to establish a single unifying code for football. The first meeting took place at the Freeman's Tavern in London. The clubs represented at the meeting included Barnes, Blackheath, Perceval House, Kensington School, the War Office, Crystal Palace, Forest (later known as the Wanderers), the Crusaders and No Names of Kilburn. Charterhouse also sent an observer to the meeting. Percy Young, has pointed out, that the FA was a group of men from the upper echelons of British society: "Men of prejudice, seeing themselves as patricians, heirs to the doctrine of leadership and so law-givers by at least semi-divine right." Ebenezer Cobb Morley was elected as the secretary of the FA. At a meeting on 24th November, 1863, Morley presented a draft set of 23 rules. These were based on an amalgamation of rules played by public schools, universities and football clubs. This included provision for running with the ball in the hands if a catch had been taken "on the full" or on the first bounce. Players were allowed to "hack the front of the leg" of the opponent when they were running with the ball. Two of the proposed rules caused heated debate: IX. A player shall be entitled to run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal if he makes a fair catch, or catches the ball on the first bound; but in case of a fair catch, if he makes his mark (to take a free kick) he shall not run. X. If any player shall run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal, any player on the opposite side shall be at liberty to charge, hold, trip or hack him, or to wrest the ball from him, but no player shall be held and hacked at the same time. Some members objected to these two rules as they considered them to be "uncivilized". Others believed that charging, hacking and tripping were important ingredients of the game. One supporter of hacking argued that without it "you will do away with the courage and pluck of the game, and it will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen who would beat you with a week's practice." The main defender of hacking was F. W. Campbell, the representative from Blackheath, who considered this aspect of the game was vital in developing "masculine toughness". Campbell added that "hacking is the true football" and he resigned from the FA when the vote went against him (13-4). He later helped to form the rival Rugby Football Union. On 8th December, 1863, the FA published the Laws of Football. 1. The maximum length of the ground shall be 200 yards, the maximum breadth shall be 100 yards, the length and breadth shall be marked off with flags; and the goal shall be defined by two upright posts, eight yards apart, without any tape or bar across them. 2. A toss for goals shall take place, and the game shall be commenced by a place kick from the centre of the ground by the side losing the toss for goals; the other side shall not approach within 10 yards of the ball until it is kicked off. 3. After a goal is won, the losing side shall be entitled to kick off, and the two sides shall change goals after each goal is won. 4. A goal shall be won when the ball passes between the goal-posts or over the space between the goal-posts (at whatever height), not being thrown, knocked on, or carried. 5. When the ball is in touch, the first player who touches it shall throw it from the point on the boundary line where it left the ground in a direction at right angles with the boundary line, and the ball shall not be in play until it has touched the ground. 6. When a player has kicked the ball, any one of the same side who is nearer to the opponent's goal line is out of play, and may not touch the ball himself, nor in any way whatever prevent any other player from doing so, until he is in play; but no player is out of play when the ball is kicked off from behind the goal line. 7. In case the ball goes behind the goal line, if a player on the side to whom the goal belongs first touches the ball, one of his side shall he entitled to a free kick from the goal line at the point opposite the place where the ball shall be touched. If a player of the opposite side first touches the ball, one of his side shall be entitled to a free kick at the goal only from a point 15 yards outside the goal line, opposite the place where the ball is touched, the opposing side standing within their goal line until he has had his kick. 8. If a player makes a fair catch, he shall be entitled to a free kick, providing he claims it by making a mark with his heel at once; and in order to take such kick he may go back as far as he pleases, and no player on the opposite side shall advance beyond his mark until he has kicked. 9. No player shall run with the ball. 10. Neither tripping nor hacking shall be allowed, and no player shall use his hands to hold or push his adversary. 11. A player shall not be allowed to throw the ball or pass it to another with his hands. 12. No player shall be allowed to take the ball from the ground with his hands under any pretence whatever while it is in play. 13. No player shall be allowed to wear projecting nails, iron plates, or gutta-percha on the soles or heels of his boots. In 1866 the offside rule was altered to allow a player to be onside when three of opposing team are nearer their own goal-line. Three years later the kick-out rule was altered and goal-kicks were introduced. Archie Hunter, who played football in Scotland in the late 1860s, later explained that "football in those days was very different to what it is now or ever will be again. There were no particular rules and we played pretty much as we liked; but we thought we were playing the Rugby game, of course, because the Association hadn't started then. It didn't matter as long as we got goals; and besides, we only played with one another, picking sides among ourselves and having friendly matches in the playground. Such as it was though, I got to like the game immensely, and I spent as much time as I could kicking the leather." In 1871, Charles W. Alcock, the Secretary of the Football Association, announced the introduction of the Football Association Challenge Cup. It was the first knockout competition of its type in the world. Only 12 clubs took part in the competition: Wanderers, Royal Engineers, Hitchin, Queens Park, Barnes, Civil Service, Crystal Palace, Hampstead Heathens, Great Marlow, Upton Park, Maidenhead and Clapham Rovers. Many clubs did not enter for financial reasons. All ties had to be played in London. Clubs based in places such as Nottingham and Sheffield found it difficult to find the money to travel to the capital. Each club also had to contribute one guinea towards the cost of the £20 silver trophy. The Wanderers won the 1872 final. They also won it the following season with with Arthur Kinnaird getting one of the goals. Other winners of the competition included Oxford University (1874), Royal Engineers (1875), Old Etonians (1879 and 1882) and Old Carthusians (1881). Charles W. Alcock, the Secretary of the Football Association, was the dominant figure in the early days of the game. As he pointed out: "What was ten or fifteen years ago the recreation of a few has now become the pursuit of thousands. An athletic exercise carried on under a strict system and in many cases by an enforced term of training, almost magnified into a profession." According to Frederick Wall, the Royal Engineers pioneered the passing game at a time when most clubs placed an emphasis on the long-ball or dribbling. To popularize football, the club toured the industrial areas of England. This included playing games in Derby, Nottingham and Sheffield. In the early part of the 19th century footballs were leather-covered bladders. There were experiments with balls made of natural rubber but they bounced too high to be used in football matches. In 1830 Charles Macintosh discovered a way of producing thin rubber sheets. This enabled the production of inflatable rubber bladders for leather footballs. During this period footballers wore any pair of leather boots in their possession. Some players nailed bits of leather to their soles to give them a better grip during games. In 1863 the Football Association introduced Rule 13 that stated: "No one wearing projecting nails, iron plates or gutta percha on the soles of his boots is allowed to play." The Football Association decided in 1872 that the football should be spherical with a circumference of 68 centimeters. It also had to be cased in leather and had to be weighed between 453 and 396 grams at the start of a game. As pointed out by The Encyclopedia of British Football: "On wet days the ball grew increasingly heavy as the leather soaked up large amounts of liquid. This, together with the lacing that protected the valve of the bladder, made heading the ball not only unpleasant but also painful and dangerous." The 1870s saw several changes to Football Association rules. In 1870 eleven-a-side games were introduced with the addition of a goalkeeper. In 1872 the FA published an updated set of laws. This made it clear that "a goal shall be won when the ball passes between the goal posts under the tape, not being thrown, knocked on, or carried." The new rules clearly distinguished between goalkeepers and other players: "A player shall not throw the ball nor pass it to another except in the case of the goalkeeper, who shall be allowed to use his hands for the protection of his goal... No player shall carry or knock on the ball; nor shall any player handle the ball under any pretence whatever." |

England against Scotland in 1877. Note the lack of crossbars and nets. |

|

1871 also saw the introduction of umpires and a neutral referee. Both

sides were allowed to appoint an umpire to whom players could appeal to

about incidents that took place on the pitch. However, the FA rule now

stated: "Any point on which the umpires cannot agree shall be decided by

the referee". The FA Cup helped to popularize the game of football. Up until this competition only fifty clubs were members of the Football Association and played by their rules. This included teams who played as far away as Lincoln, Oxford and York. The main rival to the FA was the 26-member Sheffield Association. Other football clubs were totally independent and played by their own set of rules. In 1877 the clubs in Sheffield decided to join the FA and by 1881 its membership had risen to 128. |

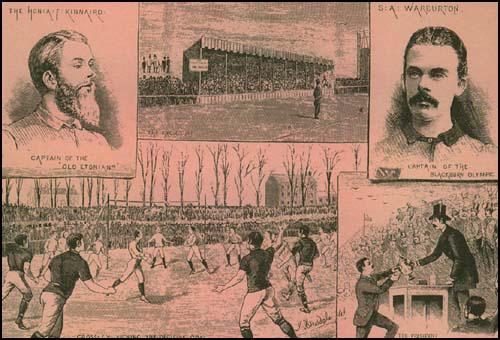

Blackburn Olympic defeating Old Etonians 2-1 in the 1883 FA Cup Final. |

|

The FA continued to adapt the rules of the game. In 1881 the Football

Association introduced a law that stated that if a player was "guilty of

ungentlemanly behavior the referee could rule offending players out of

play and order them off the ground." If a player was sent off they were

usually suspended for a month without pay. In 1882 all clubs had to provide crossbars. Ten years later goal nets became compulsory. This reduced the number of disputes as to whether the ball had crossed the goal-line or passed between the posts. |

Blackburn Olympic beat Old Etonians 2-1 in the 1883 FA Cup Final. |

|

In January, 1884, Preston North End played the London side, Upton Park,

in the FA Cup. After the game Upton Park complained to the Football

Association that Preston was a professional, rather than an amateur

team. Major William Sudell, the secretary/manager of Preston North End

admitted that his players were being paid but argued that this was

common practice and did not breach regulations. However, the FA

disagreed and expelled them from the competition. It was well-known that Sudell improved the quality of the team by importing top players from other areas. This included several players from Scotland. As well as paying them money for playing for the team, Sudell also found them highly paid work in Preston. Preston North End now joined forces with other clubs who were paying their players, such as Aston Villa and Sunderland. In October, 1884, these clubs threatened to form a break-away British Football Association. The Football Association responded by establishing a sub-committee, which included William Sudell, to look into this issue. On 20th July, 1885, the FA announced that it was "in the interests of Association Football, to legalize the employment of professional football players, but only under certain restrictions". Clubs were allowed to pay players provided that they had either been born or had lived for two years within a six-mile radius of the ground. Blackburn Rovers immediately registered as a professional club. Their accounts show that they spent a total of £615 on the payment of wages during the 1885-86 season. It was revealed that top players such as James Forrest and Joseph Lofthouse were being paid £1 a week. In 1887 Sunderland beat Middlesbrough 4-2 in an early round of the FA Cup. Middlesbrough protested that three of Sunderland's players (Monaghan, Hastings and Richardson) were living in Scotland and was lodged at the Royal Hotel at the club's expense. In January 1888, the Football Association examined the Sunderland books and discovered "a payment of thirty shillings in the cash book to Hastings, Monaghan and Richardson for train fares from Dumfries to Sunderland". Sunderland was kicked out of the FA Cup and ordered to pay the expenses of the inquiry. The three players concerned were each suspended from football in England for three months. The decision to pay players increased club's wage bills. It was therefore necessary to arrange more matches that could be played in front of large crowds. On 2nd March, 1888, William McGregor circulated a letter to Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, and West Bromwich Albion suggesting that "ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season." John J. Bentley of Bolton Wanderers and Tom Mitchell of Blackburn Rovers responded very positively to the suggestion. They suggested that other clubs should be invited to the meeting being held on 23rd March, 1888. This included Accrington, Burnley, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, Wolverhampton Wanderers, Old Carthusians, and Everton should be invited to the meeting. The following month the Football League was formed. It consisted of six clubs from Lancashire (Preston North End, Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Burnley, Bolton Wanderers and Everton) and six from the Midlands (Aston Villa, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers). The main reason Sunderland was excluded was because the other clubs in the league objected to the costs of travelling to the North-East. McGregor also wanted to restrict the league to twelve clubs. Therefore, the applications of Sheffield Wednesday, Nottingham Forest, Darwen and Bootle were rejected. The first season of the Football League began in September, 1888. Preston North End won the first championship that year without losing a single match and acquired the name the "Invincibles". Eighteen wins and four draws gave them a 11 point lead at the top of the table. The top goal scorers were John Goodall (21), Jimmy Ross (18), Fred Dewhurst (12) and John Gordon (10). Major William Sudell, had persuaded some of the best players in England, Scotland and Wales to join Preston: John Goodall, Jimmy Ross, Nick Ross, David Russell, John Gordon, John Graham, Robert Mills-Roberts, James Trainer, Samuel Thompson and George Drummond. He also recruited some outstanding local players, including Bob Holmes, Robert Howarth and Fred Dewhurst. As well as paying them money for playing for the team, Sudell also found them highly paid work in Preston. |

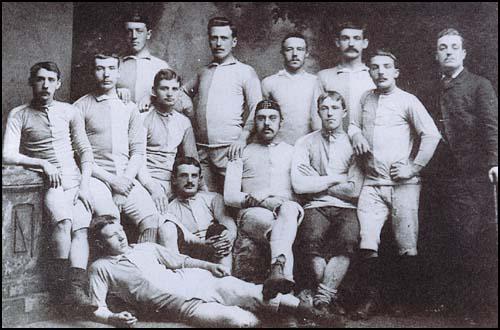

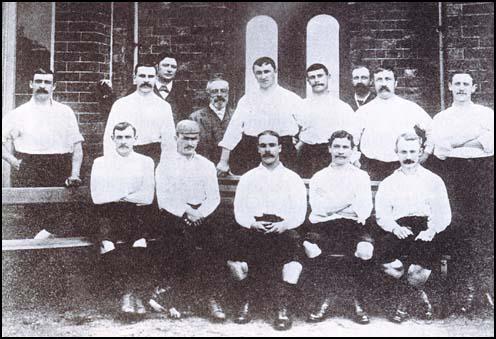

The Preston North End team that won the Football League title in 1888-89: George Drummond, Bob Holmes, John Graham and Robert Mills-Roberts are in the back row. John Gordon, Jimmy Ross, John Goodall, Fred Dewhurst and Samuel Thompson are sitting on the bench. |

|

Preston North End also beat Wolverhampton Wanderers 3-0 to win the 1889

FA Cup Final. Preston won the competition without conceding a single

goal. The club also won the league the following season. However, other

teams began to employ the same tactics as Major William Sudell. Clubs

like Derby County, Everton, Sunderland, Aston Villa, and Wolverhampton

Wanderers had more money at their disposal and could pay higher wages

than Preston. Over the next couple of years Preston lost all their best

players and they were never to win the league title again. Preston North End also won the league the following season. This time it was much closer as they only beat Everton by one point. James Trainer, John Gordon and David Russell appeared in all 22 league games and Jimmy Ross and George Drummond only missed one game. It was the last time that Preston was to win the Football League. They finished second to Everton (1890-91) and Sunderland (1892-93) but after that they ceased to become a major force in the game. Preston's top players were persuaded to sign for other clubs: John Goodall (Derby County), Jimmy Ross (Liverpool), Nick Ross (Everton), David Russell (Nottingham Forest), Samuel Thompson (Wolverhampton Wanderers), whereas Bob Holmes, George Drummond, Robert Mills-Roberts, James Trainer and John Graham retired from full-time professional football. In the 1880s football was introduced into most state schools. It could be played on any hard surface and that was especially attractive to those schools that did not have access to playing fields. As a high percentage of the children were physically underdeveloped and undernourished, soccer was considered to be more suitable than rugby. The game was encouraged by the ruling class. In 1881 Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, MP for Denbighshire, argued: "Much has been said of the British spending their time on drinking... These kinds of sports... keep young men from wasting their time... after playing a good game of football... young men are more glad to go to bed then visiting the public house." In 1888 it was reported that Nick Ross was receiving £10 a month after he was transferred from Preston North End to Everton. It is estimated that this was nearly twice that of most top players. By the early 1890s leading clubs such as Aston Villa, Newcastle United and Sunderland were paying their best players £5 a week. In September, 1893, Derby County proposed that the Football League should impose a maximum wage of £4 a week. At the time, most players were only part-time professionals and still had other jobs. These players did not receive as much as £4 a week and therefore the matter did not greatly concern them. However, a minority of players, were so good they were able to obtain as much as £10 a week. This proposal posed a serious threat to their income. The role of the referee changed in 1891. He moved onto the pitch from the touchline and took complete control of the game. The umpires now became linesmen. 1891 also saw the introduction of the penalty kick. As Dave Russell has pointed out in Football and the English (1997) that this new rule "bitterly upset many amateurs, who argued that the new legislation assumed that footballers could be capable of cheating." |

Painting by Thomas Henry of the Sunderland v Aston Villa game played in April 1895. |

|

The shoulder charge was still an important part of the game. This could

be used against players even if they did not have the ball. If a

goalkeeper caught the ball, he could be barged over the line. As a

result, goalkeepers tended to punch the ball a great deal. Until 1892

keepers could be challenged even when they were not holding the ball. A report published by The Lancet on 24th March 1894 pointed out the dangers of playing football. The doctor who wrote the article warned about the practice of charging a man trying to head a football: "To smash cruelly into him and knock him over unnecessarily and perhaps savagely is clearly a brutality and perhaps savagely is clearly a brutality which is permitted by the rules." On 23rd November 1896, Joseph Powell of Arsenal went to kick a high ball during a game against Kettering Town. His foot caught on the shoulder of an opponent and Powell fell and broke his arm. One of the men who went to his aid fainted at the sight of the protruding bone. Infection set in and, despite amputation above the elbow, Powell died a few days later when just twenty-six years of age. The Lancet continued to record details of these incidents and in an article published on 22nd April 1899 that over the last eight years around 96 men had died while playing football and rugby. In the 19th century it cost 6d to watch a Football League match. This was expensive when you compare this with the price of other forms of entertainment. It usually cost only 3d to visit the musical hall or the cinema. It has to be remembered that at this time skilled tradesmen usually received less than £2 a week. As Dave Russell points out in Football and the English: A Social History of Association Football in England (1997): "In terms of social class, crowds at Football League matches were predominantly drawn from the skilled working and lower-middle classes... Social groups below that level were largely excluded by the admission price." Russell adds "the Football League, quite possibly in a deliberate attempt to limit the access of poorer (and this supposedly "rowdier") supporters, raised the minimum adult male admission price to 6d". Men also had the problem of having to work on a Saturday. Although some trades granted their workers a half-day holiday, it did not give them much time to travel very far to see a game. Even a local game caused considerable problems. For example, West Ham United played Brentford in an important game at the end of the 1897-98 season. A local newspaper reported that because of the inadequate transport system supporters had to travel by boat from Ironworks Wharf along the Thames to Kew before catching a train to Brentford. Given these transport problems, it is no surprise that the game was watched by only 3,000 people. In September, 1898, the South Essex Gazette reported that in a game against Brentford, two West Ham United players, George Gresham and Sam Hay, "bundled the goalkeeper into the net whilst he had the ball in his hands". The goal stood because this action was within the rules at the time. |

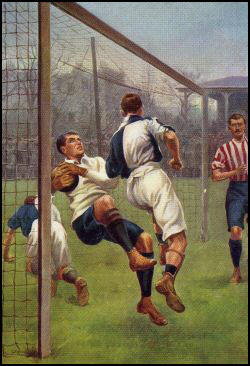

Goalkeeper being legally barged over the goal line in a game in 1904. |

|

Law 8 of the Football Association stated: "The goalkeeper may, within

his own half of the field of play, use his hands, but shall not carry

the ball." Leigh Roose, who began playing for Aberystwyth Townin the

North Wales Combination League, in 1894, developed a strategy that was

within the law but greatly increased the effectiveness of the

goalkeeper. Roose began to bounce the ball up to the half-way line

before launching an attack with a long kick or a good throw. As Spencer

Vignes points out in his book on Roose: "This was perfectly within the

letter of the law, though few goalkeepers risked doing it for fear of

either leaving their goal unattended or being steamrollered by a

centre-forward. It became a highly effective, direct way of launching

attacks and Leigh used it to his side's advantage whenever possible." Leigh Roose, who went on to play for Stoke City, Everton, Sunderland, Celtic, Huddersfield Town, Aston Villa and Arsenal, influenced a whole generation of goalkeepers. For example, Tommy Moore, who played for West Ham United, between 1898 to 1901, often moved up field and started an attack by punching the ball into the opposition half. In a game against Chesham, the game was so one-sided that Moore spent most of the game on the offensive. As the local newspaper reported: "Moore had so little to do that he often left his goal unprotected and played up with the forwards." It was the railways that eventually provided cheap and fast travel for football supporters. Over 114,000 people watched Tottenham Hotspur play Sheffield United in the 1901 FA Cup. It has been estimated that a large percentage of the crowd travelled to Crystal Palace Stadium via the London & Brighton Railway and Great Northern Railway. When Chelsea was formed in 1905 it chose Stamford Bridge as its home as it was close to Waltham Green station (now Fulham Broadway). Tottenham Hotspur benefited from its closeness to White Hart Lane railway station. It has been argued that "10,000 spectators could be easily handled by trains arriving every five minutes". In 1906 a railway station at Ashton Gate was opened to enable people to travel to the Bristol City ground. Manchester United moved to Old Trafford in 1909 to take advantage of the railway network established for the nearby cricket ground. One of the main reasons Arsenal moved to Highbury was because it was served by the London Underground station at Gillespie Road (later renamed Arsenal). Most experts consider Leigh Roose as the best goalkeeper during the period leading up to the First World War. Frederick Wall, the Secretary of the Football Association described Roose as "a sensation... a clever man who had what is sometimes described as the eccentricity of genius. His daring was seen in the goal, where he was often taking risks and emerging triumphant." Rouse was an entertainer, who carried out pranks to get laughs. This included sitting on the crossbar at half-time. The Bristol Times reported that: "Few men exhibit their personality so vividly in their play as L. R. Roose.... He rarely stands listlessly by the goalpost even when the ball is at the other end of the enclosure, but is ever following the play keenly and closely. Directly his charge is threatened, he is on the move. He thinks nothing of dashing out 10 or 15 yards, even when his backs have as good a chance of clearing as he makes for himself. He will also rush along the touchline, field the ball and get in a kick too, to keep the game going briskly." Leigh Roose played like a modern "sweeper" and spent much of his time outside his penalty area. He later wrote about this strategy: "A goalkeeper should take in the position (of the opposing players) at once and... if deemed necessary, come out of his goal immediately. He must be regardless of personal consequences and, if necessary, go head first into a pack into which many men would hesitate to insert a foot, and take the consequent grueling like a Spartan." He added that "the reason why goalkeepers don't come out of the goal more often is their regard for personal consequences." Roose pointed out a good goalkeeper should not "keep goal on the usual stereotype lines... and is at liberty to cultivate originally". According to Roose: "players with the intelligence to devise a new move or system, and application to carry it out, will go far." In his roundup of the 1901-02 season, the football journalist, James Catton, described Leigh Roose in Athletic News as "the Prince of Goalkeepers". This was a term that had previously been used to describe Teddy Doig. Roose in fact replaced Doig as Sunderland's goalkeeper in 1908. Leigh Roose soon become a strong favourite with the Sunderland fans. They liked the way he set up attacks by running out to the half-way line. Roose told a journalist that he was surprised that not more goalkeepers did not follow his example: "The law states that any (goalkeeper) is free to run over half of the field of play before ridding themselves of the ball. This not only helps to puzzle the attacking forwards, but to build the foundations for swift, incisive counter-attacking play. Why then do so few make use of it?" |

Leigh Roose playing for Stoke City |

|

George Holley, who played for Sunderland with Roose later explained why

this strategy was not followed by many other goalkeepers. "He was the

only one who did it because he was the only one who could kick or throw

a ball that accurately over long distances, giving himself time to

return to his goal without fear of conceding." Several clubs complained to the Football Association about Roose's strategy. Several committee members felt that Roose was ruining the game as a spectacle by his ability to break up creative and attacking play. However, they could not agree about what to do about it. In June 1912 the Football Association finally decided to change Law 8 that stated: "The goalkeeper may, within his own half of the field of play, use his hands, but shall not carry the ball." It now read: "The goalkeeper may, within his own penalty area, use his hands, but shall not carry the ball." In other words, if a goalkeeper wanted to move around his penalty area while handling the ball, he had to bounce rather than carry it as he went. He was also not allowed to handle the ball outside the penalty area. In 1923 the FA Cup was moved to Wembley. The ground had been built for the British Empire Exhibition and had excellent railway links. Over 270,000 people travelled in 145 special services to the final that featured West Ham United and Bolton. The railways had a considerable impact on the attendances of international matches. Only 1,000 people from Scotland travelled to watch the game against England at Crystal Palace in 1897. However, for the match at Wembley in 1936, 22,000 Scots came to London in 41 trains provided by the London Midland and Scottish Railway. |

| Source - References |

|

(1) William FitzStephen, The Life of Thomas Becket (c. 1190) After lunch all the youth of the city go out into the fields to take part in the famous game of ball. The students of each school have their own ball; the workers from each city craft are also carrying their balls. Older citizens, fathers, and wealthy citizens come on horseback to watch their juniors competing, and to relive their own youth vicariously: you can see their inner passions aroused as they watch the action and get caught up in the fun being had by the carefree adolescents. (2) George Owen, describing the playing of football in Wales (c. 1550) There is a round ball prepared... so that a man may hold it in his hand... The ball is made of wood and boiled in tallow to make it slippery and hard to hold... The ball is called a knappan, and one of the company hurls it into the air... He that gets the ball hurls it towards the goal... the knappan is tossed backwards and forwards... It is a strange sight to see a thousand or fifteen hundred men chasing after the knappan... The gamesters return home from this play with broken heads, black faces, bruised bodies and lame legs... Yet they laugh and joke and tell stories about how they broke their heads... without grudge or hatred." (3) Philip Stubbes, Anatomy of Abuses (1683) Lord remove these exercises from the Sabbath. Any exercise which withdraweth from godliness, either upon the Sabbath or any other day, is wicked and to be forbidden. Now who is so grossly blind that seeth not that these aforesaid exercises not only withdraw us from godliness and virtue, but also hail and allure us to wickedness and sin? For as concerning football playing I protest unto you that it may rather be called a friendly kind of fight than a play or recreation - a bloody and murdering practice than a fellow sport or pastime. For doth not everyone lye in wait for his adversary, seeking to overthrow him and punch him on his nose, though it may be on hard stones, on ditch or dale, on valley or hill, or whatever place so ever it be he care not, so he have him down; and that he can serve the most of this fashion he is counted the only fellow, and who but he? So that by this means sometimes their necks are broken, sometimes their backs, sometimes their legs, sometimes their arms, sometimes their noses gush out with blood, sometimes their eyes start out, and sometimes hurt in one place, sometimes in another... Football encourages envy and hatred... sometimes fighting, murder and a great loss of blood. (4) John Stow, Survey of London (1720) The lower classes divert themselves at football, wrestling, cudgels, nine-pins, shovelboard, cricket, stow ball, ringing of bells, quoits, pitching the bar, bull and bear baitings, throwing at cocks and lying at ale-houses. (5) Joseph Strutt, The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England (1801) Football is so called because the ball is driven about with the feet instead of the hands. It was formerly much in vogue among the common people of England, though of late years it seems to have fallen into disrepute, and is but little practised. I cannot pretend to determine at what period the game of football originated; it does not, however, to the best of my recollection, appear among the popular exercises before the reign of Edward III, and then, in 1349, it was prohibited by a public edict; not, perhaps, from any particular objection to the sport in itself, but because it co-operated, with other favourite amusements, to impede the progress of archery. When a match at football is made, two parties, each containing an equal number of competitors, take the field, and stand between two goals, placed at the distance of eighty or an hundred yards the one from the other. The goal is usually made with two sticks driven into the ground, about two or three feet apart. The ball, which is commonly made of a blown bladder, and cased with leather, is delivered in the midst of the ground, and the object of each party is to drive it through the goal of their antagonists, which being achieved the game is won. The abilities of the performers are best displayed in attacking and defending the goals; and hence the pastime was more frequently called a goal at football than a game at football. When the exercise becomes exceeding violent, the players kick each other's shins without the least ceremony, and some of them are overthrown at the hazard of their limbs. (6) Sheffield Playing Rules (21st October 1858) 1. The kick off from the middle must be a place kick. 2. Kick Out must not be from more than twenty-five yards out of goal. 3. Fair catch is a catch direct from the foot of the opposite side and entitles a free kick. 4. Charging is fair in case of a place kick (with the exception of a kick off as soon as a player offers to kick) but he may always draw back unless he has actually touched the ball with his foot. 5. No pushing with the hands or hacking, or tripping up is fair under any circumstances whatsoever. 6. Knocking or pushing on the ball is altogether disallowed. The side breaking the rule forfeits a free kick to the opposite side. 7. No player may be held or pulled over. 8. It is not lawful to take the ball off the ground (except in touch) for any purpose whatever. 9. If the ball be bouncing it may be stopped by the hand, not pushed or hit, but if the ball is rolling it may not be stopped except by the foot. 10. No goal may be kicked from touch, nor by a free kick from a fair catch. 11. A ball in touch is dead, consequently the side that touches it down must bring it to the edge of the touch and throw it straight out from touch. 12. Each player must provide himself with a red and dark blue flannel cap, one color to be worn by each side. (7) The Sheffield Independent (3rd January, 1862) Hallam played with great determination. They appeared to have many partisans present, and when they succeeded in "downing" a man their ardent friends were more noisily jubilant. At one time it appeared that the match would be turned into a general fight. Major Creswick had got the ball away and was struggling against great odds - Mr Shaw and Mr Waterfall (of Hallam). Major Creswick was held by Waterfall and in the struggle Waterfall was accidentally hit by the Major. All parties agreed that the hit was accidental. Waterfall, however, ran at the Major in the most irritable manner, and struck him several times. He also "threw off his waistcoat" and began to "show fight" in earnest. Major Creswick, who preserved his temper admirably, did not return a single blow. There were a few who seemed to rejoice that the Major had been hit and were just as ready to "Hallam" it. We understand that many of the Sheffield players deprecated - and we think not without reason - the long interval in the middle of the game that was devoted to refreshments. (8) The Sheffield Independent (10th January, 1862) The unfair report in your paper of the... football match played on the Bramall Lane ground between the Sheffield and Hallam Football Clubs calls for a hearing from the other side. We have nothing to say about the result - there was no score - but to defend the character and behaviour of our respected player, Mr William Waterfall, by detailing the facts as they occurred between him and Major Creswick. In the early part of the game, Waterfall charged the Major, on which the Major threatened to strike him if he did so again. Later in the game, when all the players were waiting a decision of the umpires, the Major, very unfairly, took the ball from the hands of one of our players and commenced kicking it towards their goal. He was met by Waterfall who charged him and the Major struck Waterfall on the face, which Waterfall immediately returned. (9) Archie Hunter, Triumphs of the Football Field (1890) I was christened in the courthouse of the prison because at that time the church was undergoing repairs and could not be used for the ceremony. Not far from Joppa my father had a farm, but he died while I was too young to remember him; and before I was many years older the family removed to Ayr, where I was sent to school. My three brothers - all dead now - were athletes, and I suppose the love of good, hearty games ran in our blood. The excellent country air, and the rural life we led, gave us plenty of strength and fitted us for out-door sports. It wasn't long before I was playing football at school with the other lads; but football in those days was very different to what it is now or ever will be again. There were no particular rules and we played pretty much as we liked; but we thought we were playing the Rugby game, of course, because the Association hadn't started then. It didn't matter as long as we got goals; and besides, we only played with one another, picking sides among ourselves and having friendly matches in the playground. Such as it was though, I got to like the game immensely, and I spent as much time as I could kicking the leather. We were a merry lot, but by and by I had to leave school while I was still very young, and I was rather sorry, I can assure you. I was sorry to go, but I wanted to continue playing, so I joined the Ayr Star Football Club, which was then a Rugby Union team and for a short time I played the strict Rugby game. After playing the season under the Rugby rules we held a meeting, not, as you might think, in some comfortable room, but under the blue canopy of heaven, and by lamp-light; and after considerable discussion we determined to alter the name of the club from the 'Star' to the 'Thistle'. But there was soon to be a great change. The Queen's Park, the leading club in Scotland, adopted the Association rules almost as soon as they were made and of course, most of the other clubs began to follow the example. The 'Thistle' Club was one of them. I had only played in two matches under the old code, officiating as full back... but now we began to practise dribbling... And we went in for the new game with enthusiasm, I can tell you. Every other night saw us in hard training, and we learnt the art of working well together. In my opinion that is the secret of success. Good combination on the part of the players is greatly to be preferred to the muscular powers of one or two of them. Strength has got very little chance against science. (10) Frederick Wall, 50 Years of Football (1935) Some seventy years ago those who played Association football in England were generally regarded as harmless lunatics. Men shrugged their shoulders and said: "If they hurt anybody it will only be themselves, and the fewer lunatics the better." That is an impression given me by a man who was enjoying a football frolic when I was a child. It seems to me as if football has always had detractors and scoffers. Royalty, Parliament, bishops and puritans for centuries tried to prevent the rough revels of parish against parish, when the playing area was a large track of country and town, with a millwheel and a church-door, miles apart, as the goals! An encounter of this character would frighten most modern players. Possibly these rude games were the forerunners of the football that the old-foundation public schools developed according to the size and nature of their playgrounds. All the various rules of these schools were carefully considered by a body of gentlemen at Cambridge University. These enthusiasts, trying to work out a code that all could play under, whatever may have been their school, produced a set of rules or laws of play that the Football Association, founded in 1863, took as a model for the game they wished to popularize. It is not necessary to enlarge this summary by details. Suffice it to say that the parent body, as it is now called, gradually evolved the laws under which most civilized nations now play what I like to speak of as "our game." During the fifty years from 1863 to 1913 this form made a great advance and became the national winter game of all Britain. (11) Graham McColl, Aston Villa: 1874-1998 (1998) The influence of Ramsay, then Hunter, led Villa to develop an intricate passing game, a revolutionary move for an English club in the late 1870s. It was a style of play modelled on that which was prevalent in Scotland at the time which was prevalent in Scotland at the time and which had been pioneered by Queen's Park, the Glasgow side. This type of sophisticated teamwork had rarely been employed in England. Instead, individuals would try to take the ball as far as they could on their own until stopped by an opponent. (12) James Walvin, The People's Game (1975) Those who wished to encourage sporting activity among working people, the ex-public-school men keen to tackle the problems of industrial Britain, needed a point of entry to a social world which was often distant and generally alien. One of the most useful means of approaching working-class life was via the Church, of all denominations. Of course among many of the clergy belief in athleticism was almost as striking as their belief in God (one prominent headmaster had said, "the Laws of physical well-being are the laws of God"). Few doubted the needs for large-scale recreation as part of the Churches' solution to the nation's ills. Clergymen seized on football as an ideal way of combating urban degeneracy. Robust games could, they believed, bring strength, health and a host of qualities badly needed by deprived working people - especially the young. As a result, working-class churches began to spawn football teams in the years immediately following the concession of free Saturday afternoons in local industries. Liverpool, which before the turn of the century was to establish itself as the footballing centre of England, was later than other cities in turning to the game, but when, in 1878, local teams began to form, they sprang most notably from churches, headed by St Domingo's, St Peter's, Everton United Church and St Mary's, Kirkdale. As late as 1885, twenty-five of the 112 football clubs in Liverpool had religious connections. Similar patterns emerged in other cities. In Birmingham in 1880, eighty-three of the 344 clubs (some twenty-four per cent) were connected to churches. Indeed many of today's famous clubs began life as church teams. Aston Villa originated in 1874 from members of the Villa Cross Wesleyan Chapel who already played cricket but wanted a winter sport. Birmingham City began life as Small Heath Alliance, organized by members of Trinity Church in 1875. Some years before, pupils and teachers of Christ Church, Bolton, formed a football club. In 1887 they took the name Bolton Wanderers. Blackpool FC emerged from an older team based on the local St John's Church. Similarly, Everton started life in 1878 as St Domingo's Church Sunday School (and later produced an offshoot which became Liverpool FC). In 1880 men at St Andrew's Sunday School, West Kensington, organized a football team which later became Fulham FC. Members of the young men's association at St Mary's Church, Southampton, formed a team in 1885, changing the name to that of the present professional club in 1897. In Swindon, the local football team owed its origins to the work of the Revd W. Pitt in 1881. A year later members of the Burnley YMCA turned to football. Boys at St Luke's Church, Blakenhall, formed a football team in 1877, later taking the name Wolverhampton Wanderers. These surviving professional teams constitute only a small minority of the thousands of teams founded in the 1870s and 1880s from church organisations (often with the local vicar or curate as a player). It might seem a contradictory point to note that one of the other main institutions which spawned football teams in these years was the local pub. This, after all, had been the traditional centre for a host of plebeian pleasures for centuries past. Pubs offered a place to meet, somewhere to change, a venue for news and information; a place where teams, management and supporters convened (much in fact as they still do throughout Britain). (13) Peter Lupson, Thank God for Football (2006) "I believe that all right-minded people have good reason to thank God for the great progress of this popular national game." Those words were spoken by the legendary Lord Arthur Kinnaird, the holder of the still unbeaten record of nine FA Cup Final appearances and the longest serving chairman in the FAs history. Kinnaird, one of the leading Christian figures of the late Victorian era, would not have spoken those words lightly. As one of the pioneers at the forefront of football's amazing development from an amateur sport played by a small number of well-to-do enthusiasts to the country's national game enjoyed by countless thousands, he was able to look back with gratitude on all that had been achieved and thank God for it. Remarkably, of the 39 clubs that have played in the FA Premier League since its inception in the 1992-93 season, 12 also have good reason to take Lord Kinnaird's words to heart - they owe their very existence to churches. But these same clubs know very little about the circumstances that led to their birth or the people involved. This is hardly surprising in view of the fact that church teams, when they started, were the equivalent of today's public parks teams and did not keep extensive records of their activities. How could they possibly have guessed that one day they would become famous and that details about their founders, match results, players' records, minutes of early meetings, etc., would be of enormous interest to thousands of their future supporters? Furthermore, much of the limited source material that was once available has since been irretrievably lost through fire or neglect. (14) Archie Hunter, Triumphs of the Football Field (1890) I am convinced that it (football) will maintain its position as the most popular game in this country and that it will remain at the head of scientific sports. There is one enthusiasm for cricket and another for football and the enthusiasm for the latter game appears to me to be excited by deeper and heartier feelings. At all events I have no fear that football will decline, though I am sorry that it is so largely maintained by the professional element. Speaking as a professional myself, I may say that I can only look upon professionalism as an unavoidable misfortune. While it is of immense assistance to the game in many respects, it appears to me that it lowers its character and I myself should have felt happier very often if I could have continued to play as an amateur and so regarded the game as a game and not as a business. However, this is a matter for the Association to deal with. I should like, as one who has been credited with some success in dealing with a football team, to offer a little advice to captains - to those who are not accustomed to their duties yet, or who may be called upon at some future time to assume the position. First and foremost I would impress this upon them - treat the players as men and not as schoolboys. I have seen a great deal of mischief resulting from neglect to do this. When the players are only treated as boys they are apt to regard themselves as boys and act accordingly. They become selfish, obstinate and quarrelsome, turn sulky if they are displeased, or wrangle with one another on the field. Insubordination can never be provided against unless every player is made to feel that he will be called to account as a man and I am certain that this system works well. Then let all prejudices be avoided. I have known Scotchmen or Welshmen disliked by Englishmen simply on account of their nationality and I have known Scotchmen and Welshmen act just in the same way towards Englishmen. Now these prejudices ought to be stamped out. The team, however it is composed, must play as a team and not as a gathering of different men out of harmony with each other. I always tried to foster good feeling in Aston Villa and I think we were one of the merriest and happiest teams in the country. For myself I never bothered my head about the country a man came from and as long as we had good players and good fellows among us, it mattered not whether they were English, Scotch or Welsh. As to guiding the players, I think a captain should make it one of the first rules that every man should get into the habit of defending his position. I greatly dislike to see men scampering wildly over the field, leaving their places unprotected, forgetting their own particular duty and doing another man's work. If a man is playing back let him remember that and single out his opponent and be prepared to tackle him whenever the opportunity arises. We won the match with the West Bromwich Albion through sticking to this plan and I think many more matches would be more evenly contested if the custom were more generally adopted. The greatest mistake which players are in the habit of making and one which I most often cautioned my team about, is (his: when they think there is a foul, or that somebody has played off-side, they stop dead in their play and wait for the referee's decision. This has lost many a match that should have been won. Young players especially cannot be told too often that it is not they who can stop the game and however sure they may be that an appeal will be supported, they must on no account relax their efforts until the whistle sounds. I have seen many times, at a doubtful point in the game, the ball rushed through goal simply because no opposition has been offered and then, perhaps, the referee has decided that the game ought to have been continued and allowed the goal. Most clubs have suffered in this way and I would earnestly impress upon footballers the necessity of playing their hardest until a definite order is given to them to cease. |

| +-+ BACK TO TOP +-+ | |