|

|

| This Web Site is dedicated to the Memories & Spirit of the Game as only Ken Aston could teach it... |

| Enjoy, your journey here on... KenAston.org |

| Ken Aston Referee Society ~ Football Encyclopedia Bible |

|

BLANK TEMPLATE - ADMIN PAGE Administrators and Managers

|

|||

| Source - References | |||

|

|||

|

|||

|

The following season Cullis played in the games against Scotland (0-1),

France (4-2), FIFA (3-0), Norway (4-0) and Northern Ireland (7-0).

Wolves also did well in the Football League finishing as runners-up to

Everton in the 1938-39 season. In the 1938-39 season Wolves once again finished second to Arsenal. That season saw the debut of teenagers, Billy Wright and Jimmy Mullen. Wolves also enjoyed a good run in the FA Cup and beat Leicester City (5-1), Liverpool (4-1), Everton (2-0), Grimsby Town (5-0) to reach the final against Portsmouth at Wembley. Wolves lost the final 4-1. Major Buckley's Wolves became the first team in the history of English football to be runners-up in the sport's two major competitions in the same year. Stan Cullis was knocked unconscious during a game against Everton in the 1938-39 season. He suffered severe concussion that required intensive medical care. His doctors warned him that another serious concussion could kill him. |

|||

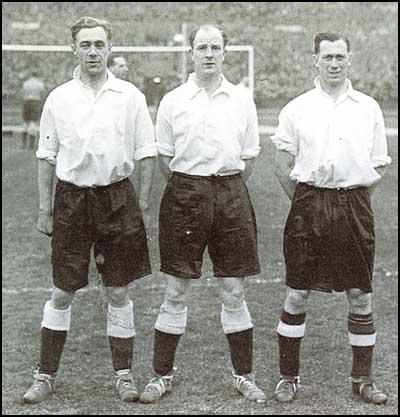

Stan Cullis before a match with Sheffield United. |

|||

|

Stanley Matthews claimed in his autobiography that Cullis was the best

header of the ball in the Football League. Tommy Lawton argued that

Cullis was "the greatest centre-half I have met". He added: "He had the

resilience of a concrete wall, the speed of a whippet, and the footwork

of a ballet dancer... He was a footballer, so he spiced his stopper role

with some daring raids into enemy territory." Stan Cullis was appointed captain for England's game against Romania on 24th May 1939. He was only 22 and was therefore the youngest player to obtain this honor. It was his 12th international cap. The England team that day included Wilf Copping, Len Goulden, Tommy Lawton, George Male, Frank Broome, Joe Mercer and Vic Woodley. |

|||

England's half-back line of Cliff Britton, Stan Cullis and Joe Mercer played for Aldershot during the war. |

|||

|

On Friday, 1st September, 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of

Poland. On Sunday 3rd September Neville Chamberlain declared war on

Germany. The government immediately imposed a ban on the assembly of

crowds and as a result the Football League competition was brought to an

end. On 14th September, the government gave permission for football

clubs to play friendly matches. Cullis joined the British Army and like many professional footballers, he became a Physical Training Instructor, and did not see any action during the war. He played in 20 wartime internationals, including 10 as captain. He also played friendly games for Wolves, Aldershot, Fulham and Liverpool. In one game a tremendous shot hit him in the face. Once again he suffered from severe concussion and was on the danger list for five days. Cullis continued to play for Wolves after the war but he was warned by a doctor that because of his previous head injuries, even heading a heavy leather football could prove fatal. Cullis, who had played 155 games for Wolves decided to retire from playing football. |

|||

Stan Cullis recovering from concussion after a match against Middlesbrough in 1947. |

|||

|

In June 1948 Cullis was appointed manager of Wolves. Cullis insisted

that his team should play at a higher tempo than the opposition. He

believed that this would pressure them into making mistakes during the

game. For this strategy to work, the Wolves players had to be fitter

than other clubs. Cullis introduced a new training regime that involved

tackling commando-like assault courses. Each player was given specific

targets. Minimum times were set for 100 yards, 220 yards, 440 yards, 880

yards, 1 mile and 3 miles. All the players had to be able to jump a

height of 4 feet 9 inches. Cullis gave his players 18 months to reach

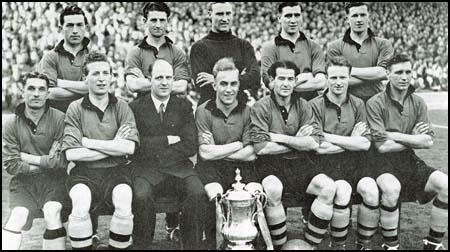

these targets. In 1949 Stan Cullis led Wolves to the FA Cup final against Leicester City. The team for the final included Johnny Hancocks, Sammy Smythe, Jesse Pye, Jimmy Dunn, Jimmy Mullen, Billy Crook, Roy Pritchard, Billy Wright, Bert Williams, Bill Shorthouse and Terry Springthorpe. Wolves won the game 3-1 with Pye scoring two goals in the first-half and Smythe netting a third in the 68th minute. |

|||

The Wolves team that won the FA Cup victory in 1949 against Leicester City. Back row (left to right): Billy Crook, Roy Pritchard, Bert Williams, Bill Shorthouse,Terry Springthorpe. Front row: Johnny Hancocks, Sammy Smythe, Stan Cullis, Jesse Pye, Jimmy Dunn and Jimmy Mullen. |

|||

|

In his first season at the club, Cullis led Wolves to FA Cup victory

over Leicester City. The following season Wolves finished in 2nd place

in the First Division. In May 1950, Cullis signed Peter Broadbent from Brentford for a fee of £10,000. As Cullis later pointed out: "The club paid a big fee to Brentford for the transfer of Peter Broadbent, a 17-year-old inside-forward from Dover, who, I thought, could well develop into one of the outstanding inside-forwards of his day. Broadbent, in addition to the normal qualities of an inside-forward, also had considerable pace, and a flair for going past a defender in the fashion of a winger." Peter Broadbent made his debut against Portsmouth in March 1951. He joined a team that included Johnny Hancocks, Sammy Smythe, Jesse Pye, Jimmy Dunn, Jimmy Mullen, Billy Crook, Roy Swinbourne, Roy Pritchard, Billy Wright, Bert Williams, Bill Shorthouse and Terry Springthorpe. He held his place in the team for the rest of the season. In the 1952-53 season Wolves finished in 3rd place in the First Division. Peter Broadbent formed a great partnership with Johnny Hancocks. As the manager, Stan Cullis, pointed out in his autobiography, All For the Wolves (1960): "We often used him (Broadbent) as an advanced winger lying on the touchline twenty yards or more ahead of Hancocks. When the ball came out of defence to Hancocks, he was able to chip it accurately to Broadbent who was frequently clear on his own. This stratagem, designed to make the fullest use of the best qualities of both players, was also extremely successful, for the full-back marking Hancocks was caught between two men and played out of the game." Wolves won the First Division championship in the 1953-54 season with Johnny Hancocks as the club's top scorer. Broadbent scored 12 goals that year. The following season the club finished second to Chelsea. In March 1956 Stan Cullis signed Harry Hooper from West Ham United for a club record fee of £25,000. Cullis wanted him as a replacement for Johnny Hancocks. Cullis later commented that: "Like Hancocks, Hooper was fast, direct, able to play on either wing and was both accurate and powerful in his use of the ball with either foot. In short, he was an ideal winger." In March 1956 Cullis signed Harry Hooper from West Ham United for a club record fee of £25,000. Cullis wanted him as a replacement for Johnny Hancocks. Cullis later commented that: "Like Hancocks, Hooper was fast, direct, able to play on either wing and was both accurate and powerful in his use of the ball with either foot. In short, he was an ideal winger." In the opening game of the 1956-57 season, Jimmy Murray scored 4 goals in a 5-1 defeat of Manchester City and ended the season with 17 goals in 33 games. In 1957 Norman Deeley replaced Harry Hooper on the right-wing. Cullis argued that: "At Molineux, Hooper found it extremely difficult to adapt himself to our style. He played several outstanding games for us but there was no doubt that he did not carry out our tactical principles to the extent I considered was essential." Norman Deeley joined a forward-line that included Jimmy Mullen, Jimmy Murray, Peter Broadbent and Bobby Mason. As Ivan Ponting pointed out: "He compensated amply in skill, determination and bravery for what he lacked in physical stature." When Wolves won the League Championship in 1957-58, Jimmy Murray was the club's leading scorer with 32 goals in 45 games. This included hat-tricks against Birmingham City (5-1) Nottingham Forest (4-1) and Darlington in the FA Cup ( 6-1). Norman Deeley scored 23 goals in 41 appearances that season. This included a spell of 13 in 15 outings during the autumn. Wolves also won the FA Cup in 1960 with Norman Deeley scoring two of the goals in the 3-0 victory over Blackburn Rovers. Deeley later recalled he could have had a hat-trick: "Barry Stobart made a good run down the left and got to the byline and whipped a cross in. I'd charged down the middle and Mick McGrath, the Rovers left-half, went with me. He actually reached the ball just before I did by stretching and sliding. With their keeper coming out to collect the cross I watched as the ball beat the keeper and rebounded off McGrath and into the net. It didn't really matter as I would have scored anyway." In the 1960-61 season Wolves finished in 3rd place behind Tottenham Hotspur. The following season they finished 5th. Cullis was surprisingly sacked in September 1964 after Wolves finished in 16th place in the league. Cullis worked as a sales representative until being appointed manager of Birmingham City in December 1965. At the time the club was struggling in the Second Division. Cullis failed to get them promoted and in March 1970, he retired from football. Stan Cullis died on 28th February 2001. |

|||

| Source - References | |||

|

(1) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960) I was an ambitious inside-forward who earned a place in the town's schoolboy team. I was not the only person who was later to lose his urge to score goals. The centre-forward in the same side was Joe Mercer, who later emerged as one of the finest wing half-backs in English football history. I was born in Ellesmere Port in October 1916, the son of Wolverhampton parents who were among the hundreds who moved out to Ellesmere Port with the Wolverhampton Corrugated Iron Company. Therefore it was natural that my father insisted that, if I became a professional footballer, it would be with Wolves. Several scouts from Football League clubs came to watch the Ellesmere Port schoolboys' team, but none of them was ever allowed to talk to me. My father always told them, "When I consider my boy is good enough, he will join Wolverhampton Wanderers." So, as Joe Mercer moved off to Everton, I stayed behind to play with the Ellesmere Port Wednesday side and, as a lad of 16, I won my first honour with them at Anfield, the Liverpool ground-a runner's-up medal in the Liverpool Hospital Cup. (2) Stan Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949) For many people, Stanley Cullis is the centre-half above all others. His willingness to take a risk by holding the ball in his own penalty area, by his ability to go up-field in a long dribble, and by his astute captaincy, he was outstanding-but people still argue whether it was all for the best... Under the old off-side law, Stan Cullis would probably have ranked as one of the greatest centre-half-backs of all time, although only the old-timers can say how he compared with Charlie Roberts, Joe McCall, Frank Barson, Alex Raisbeck, and other great ones of bygone days. (3) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960) Probably because of the precedent set by Major Buckley, Wolves have always set a high value on captaincy. Until he retired in 1959, Billy Wright, the England skipper, was one of the best captains in the Football League-and he, like myself, served his apprenticeship under the Major. Billy, too, began as an inside-forward and graduated to centre-half from the wing-half-back position. Throughout the middle years of the 1930's, Major Buckley steadily built up the team he believed would capture most of the honours in England. From the large numbers of lads he brought to Molineux for trials, he signed enough professionals both to form his team and to bring in a fortune from the transfer market. At a time when a five-figure transfer fee still astounded the football public, Major Buckley earned £130,,000 for Wolves in five years before the 1939-45 war. This spell established Wolves as one of the wealthiest football clubs in Britain. One by one, he introduced his youngsters into the First Division side until, in 1937, I was playing in a team which had grown up with me through the Birmingham Combination side and the reserves. The Major had done a wonderful job and I am sure that if war had not come in 1939, this Wolves' team would have developed quickly into one of the finest in the history of the game. The team-sheet pinned up by the Major in the dressing-room usually read: Scott; Morris, Taylor; Galley, Cullis, Gardiner; Burton, McIntosh, Westcott, Dorsett and Maguire. Although I captained the Wolves' First Division side at 19, it was in the week of my 20th birthday that I was made official captain of the club and one of my first matches in this exalted position provided a memory which will never leave me. It was on 7 November 1936 when we were beaten 2-1 by Chelsea at Molineux. After the game a section of the crowd stormed on to the pitch, uprooted the goal-posts and, amongst other things, more or less demanded the Major's head on a charger. Apart from the fact that the team was not doing particularly well, some of the supporters were upset at his transfer activities. The manager himself was away on a scouting expedition and found a policeman waiting to escort him safely home when he returned to Wolverhampton the same evening. Someone had apparently feared that a 'reception committee' might await him. The Major dismissed the policeman and walked home alone. The indignation soon died down as the team struck a winning vein and finished fifth in the First Division. In 1938, two years later, the transfer of Bryn Jones brought another wave of protest from our supporters. He went to Arsenal for a reported fee of £14,000, £4,000 more than the previous highest fee in the game's history. The modest quiet Welshman who now has a newspaper shop near the Arsenal ground came to Wolves on trial from Merthyr and quickly developed into an outstanding inside-forward with an uncanny sense of ball-distribution and ability to find the open spaces. The morning he had his trial there was a representative of a rival club waiting near the Molineux ground to sign him if Wolves turned him down. The Major, who had a great memory for faces, made quite certain Bryn did not leave the ground until he had signed on the dotted line. Mr. George Allison, the Arsenal manager, saw him as the natural successor to Alex James as the key man in Arsenal's style. The size of the fee... probably weighed heavily on a man who was not attuned to the glamour and publicity of Arsenal. If Bryn had been able to return to Molineux when the critics began to write him off, I am sure he would have recaptured the form which made him one of the greatest of inside-forwards. The Major himself did not lack a sense of publicity at this time or, for that matter, at any other time. When he introduced injections for the players at Molineux, the Press carried huge headlines on the sporting pages saying that Wolves were having "monkey gland" treatment. Whether or not monkeys came into the picture I do not know. The injections, which were something quite new in football, were nothing more potent than an immunization against the common cold, and certainly I do not think they ever helped or hindered me. Only Dickie Dorsett, I believe, refused the treatment, although several more players gave it up before the end of the course because it appeared to them to have no effect. The use of a psychologist also created something of a sensation. On the Major's instructions, I attended the psychologist's surgery in Wolverhampton on some half a dozen occasions. So far as I could gather, he tried to build up my confidence through an analysis of my worries and problems which, at this stage of my career, were not very many. In one case, I remember, the psychologist did appear to have considerable success with one player who was completely out of form. He had lost his place in the first team after the spectators had barracked him and his confidence was low. Buckley sent him to the psychologist and the results surprised us all. In no time, he had recovered his old zest and soon fought his way back into the First Division side. Now, of course, we can see that the Major was many years ahead of his contemporaries. Injections are commonly used against the common cold in all walks of life. Meanwhile, in the World Cup of 1958, Brazil brought their own psychologist all the way from South America in order to keep the team in top mental shape and won the competition in magnificent fashion. So, in April 1939, just five years after I first reported at Molineux, I found myself captain of a Cup Final team who were perhaps the strongest favorites ever to walk out on the green Wembley turf. This Final, the last held before Europe became a battlefield for the world, is still quoted to-day as a fine example of the uncertainty of Cup football. Wolves, second in the League table, needed only to go through the formality of arriving at Wembley to beat Portsmouth according to most of the critics. Certainly we felt confident that we could defeat a team who stood near the bottom of the Division. But Wolves fell ingloriously and lost by 4-1. To rub salt into the wound, one of Portsmouth's goals was scored by Bert Barlow, the inside-left whom Major Buckley had sold to them earlier in that same season. Many thousands of words have been written on the reasons for Wolves' downfall in this match. Jimmy Guthrie, the Portsmouth captain, is alleged to have said that his players knew we had nerves when an autograph book which we had signed before the match went into the Portsmouth dressing¬room. Our signatures were supposed to be spidery and shaky. But I suspect this discovery was made after the match. Other writers claimed, in the inevitable inquests, that it was a mistake for the team to remain in Wolverhampton until the morning of the match, finally to travel to Wembley amid considerable pomp and excitement. There are arguments, of course, on both sides in this matter and I don't think the Major's decision to stay at home until the last minute was the decisive cause of our defeat. Although I believe we would have beaten Portsmouth in ninety-nine matches out of a hundred, it seems that the Wolves of 1939 were destined to become another name on the long list of clubs who have fallen between the twin stools of the Championship and F.A. Cup. This chase for the `double', which has not been achieved for nearly sixty years, imposes a great strain upon the players, and the gods of Football never seem to view kindly the efforts of clubs who try to scoop the pool. As we walked off Wembley's pitch, bitterly disappointed, we consoled ourselves with the time-honored thought of the losing side-there is always next year. But, in 1939, there was no next year in the football sense. When next April came around, most of the 22 players who fought out that memorable Final found themselves in services camps far removed from Wembley. (4) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960) The trouble started in 1938 at Goodison Park, Liverpool, when I collided with Bentham, the Everton centre-forward. It was a complete accident which would not produce any serious consequences in a million other instances. But I was carried off on a stretcher and spent seven days in bed recovering from concussion. Four or five years later, I played for the British Army against the Scottish Army on the same ground. I was standing on almost the identical patch of turf where I had collided with Bentham when a fierce shot from one of the Scottish forwards caught me on the chin. Again I was carried off, with even more serious consequences, for I spent five days on the danger list in a Liverpool hospital and, altogether, I was on my back for nearly a fortnight. When I returned to Molineux in 1945, I resolved that a repetition of these incidents could only have one ending - complete retirement from football. My first game in the old gold-and-black shirt of the Wolves after the war was at Luton in a League South fixture. I remember that day well because I was given "the bird" by the crowd. Hugh Billington, the Luton centre-forward who later went to Chelsea, certainly had the better of the tussles at Kenilworth Road but this treatment from the Kenilworth Road crowd - they invariably remind me of it even to-day was not a happy augury for my return to peace-time football. Then, at Middlesbrough, I went down with concussion once again. The ball, this day, had become heavy and covered with ice from the frozen pitch and, in the course of an exciting match, I was constantly heading it. I later collapsed and was taken from the train at Sheffield on the way home and I spent a week in hospital. There I was examined by the specialist who had recently been consulted by Bruce Woodcock, the Doncaster heavyweight boxer who held the championship of Great Britain. This doctor confirmed my fears when he said that, although I could possibly play for a few more years, he advised me to retire at once. I was only thirty and the thought of retiring so early from the game I loved made me most unhappy. After considerable thought, I decided to compromise. I would play one more season and, however hard the wrench, I would retire while I was still somewhere near the top of the tree and reasonably well. (5) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960) Against Hungary, England finally crashed by six goals to three and the medicine was repeated in Budapest the following May when we lost by seven goals to one. There was no doubt that we were a weak footballing nation, a lesson which was impressed forcibly upon managers, players and spectators by the visit of the Hungarians to Wembley. This game, which aroused more public interest than any other in my lifetime, had many and tremendous effects on British football. I am not sure that all of them were for good and I shall develop that point at some length for it appears to me to be important. The defeats by the Hungarians, however, did hasten the development of a brand of attacking football to replace the negative, defensive thinking which had threatened to strangle the game. It was at this stage that I noticed several clubs were starting to introduce tactical ideas we had employed at Molineux ever since the days of Major Buckley. As the game still lacked great individual stars, managers were compelled to devise a utilitarian brand of attacking football in which goals were produced more by good team-work and good tactics and less by the brilliance of a Stanley Matthews, a Tom Finney, a Raich Carter or a Jimmy Hagan. At Molineux, the Major had used similar principles in the construction of his team which threatened to dominate English football at the outbreak of war. Just as Herbert Chapman of Arsenal set the pattern of football in the z93o's when he introduced Herbie Roberts as a defensive centre-half or third-back, so Buckley perhaps introduced the fashion for the 1950's when he devised a quick, forthright style in which frills were reduced to a minimum in the search for a maximum amount of efficiency. One consequence was the rapid growth of the "two centre-forward" system or, as it is sometimes called, the `poacher' inside-forward and the death of the old WM formation which had long been the basis of football tactics both in England and abroad. The W of the WM formation denoted a forward formation of two wingers and a centre-forward lying upfield while two inside-forwards playing behind the rest of the line represented the bottom prongs of the W. Similarly the M referred to the defensive positions with two wing-half-backs lying slightly farther upfield than the two full-backs and the centre-half. Few clubs varied these formations before the war although Major Buckley discarded the W system when he introduced Dick Dorsett to inside-forward in place of Bryn Jones. Dorsett possessed one of the hardest shots in football and, alongside Dennis Westcott, he scored many goals. These two provided one of the first instances of the "double centre-forward" plan. (6) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960) Sammy Smythe, who was in the Wolves' forward line which won the F.A. Cup Final at Wembley in 1949, provides a fine example of this contention. Smythe had certain limitations as a footballer, for he was a shade on the slow side and was certainly not in the class of Hagan, Carter or Mamiion as a ball-player. For a while, he had been playing an ordinary inside-forward's game, linking attack and defence, without making any great impression. At the start of the 1948-9 season, I thought that Smythe could do for Wolves what Dorsett had done for them before the war. With my coaches at Molineux, I worked hard to persuade Smythe that his best contribution to Wolves could be made as a "poaching" inside-forward and we used him in this style from the start of the season. Despite his slight lack of pace, Smythe was an immediate success, for he scored twenty-two goals in that season including his memorable effort in the Final against Leicester City. Then he beat several defenders before he put the ball into the net for a goal which many people recall as one of the finest ever scored at Wembley. Smythe at once became a most useful member of the Wolves' team and his goals brought him caps for Northern Ireland. He will always stand out in my mind as a fine example of the fact that correct tactics can enable an average player to make an outstanding contribution to a team because he operates with a maximum efficiency. The basic pattern of tactics which I try to employ at Molineux is almost elementary and yet I am surprised that many people in football fail to see the wood because of the trees. Under Buckley, I learned the fundamentals of the football which Wolves aim to produce to-day. The Major, seeking to remove every unnecessary frill from the game, taught us to cut out every hint of over-elaboration; not to dribble unless we were forced to; not to make two passes when one was enough. Today those principles remain as invaluable as they were twenty years ago. The primary duty of a team is to entertain the public and, for entertainment, the people of Wolverhampton demand first of all that Wolves should score at least one more goal than their opponents. Before Wolves can score a goal, we must have the ball somewhere in the region of the other team's goal and the more often we have it in that part of the field, the more goals we are likely to create. Consequently, our plan of play is designed to send the ball into the other side's penalty-area with a minimum of delay and to keep it there for as long as possible. The best method of achieving this end is to ensure that every pass is if, possible, decisive and long rather than pretty and short. Every full-back who plays for Wolves is instructed to find one of his forwards with the pass if he can. Short cross-field passes do not meet with my approval and back-passes are frowned upon severely unless, of course, the circumstances of the moment leave the player with no alternative. For many years the traditional build-up of attack in English football has seen the full-back pass to the half-back and the half-back, after engaging perhaps in a pointless exchange of passes with another half-back, ultimately sends the ball up to his forwards who, in turn, try to establish another little movement before they reach the penalty-area. I believe, however, that it is necessary to put the ball into the opponents' penalty-area from any quarter of the field in a maximum of three passes-and preferably in two, or, better still, one. Already, in my playing days at Wolves, we had begun to cut out the wing-half-back as an essential instrument of the attack. As the centre-half, or third back, I was always ordered by Major Buckley to play the ball quickly to Bryn Jones, the inside-left whose job was to transfer it into a shooting position for a colleague with the utmost speed. Although Arsenal employed a similar plan with Alex James at this time, most of the leading English clubs used a slower method of attack-building and, indeed, still do so to-day. The whole style of play at Molineux is geared towards keeping the ball in the opponents' goal-area for as long as is possible and, if this style of play involves many long kicks from out of our defence, we must accept the label that we are a team which plays "scientific kick-and-rush football". The critics who are ready to brand us in this fashion did not use such caustic terms when the same tactical plans enabled us to build up long spells of severe pressure against Honved of Budapest and Moscow Spartak in the two floodlight games at Molineux which thrilled the millions of people who watched on television. In each game, Wolves hammered away throughout the second half, offering the defences of these two fine teams from behind the Iron Curtain scarcely a moment of respite in forty-five minutes. We scored three goals in the second half against Honved, the Hungarian champions, to win by 3-2, and four against Spartak, the leading Russian side of the day. (7) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960) Often Mullen and Hancocks would find one another with long passes which travelled from one touchline to the other twice during the course of an attack. When the ball came into the middle, the defense was often caught in a line straight across the field and Swinbourne, Wilshaw or one of the other forwards was presented with a reasonable chance to score. At the end of the 1949-50 season, in which we concentrated hard on improving the efficiency of these two fine wingers, Wolves finished second in the Championship, losing first place to Portsmouth only on goal-average. In later seasons, we were able to gain further advantages from Hancocks's ability to place his passes so accurately. The club paid a big fee to Brentford for the transfer of Peter Broadbent, a 17-year-old inside-forward from Dover, who, I thought, could well develop into one of the outstanding inside-forwards of his day. Broadbent, in addition to the normal qualities of an inside-forward, also had considerable pace, and a flair for going past a defender in the fashion of a winger. Consequently, we often used him as an advanced winger lying on the touchline twenty yards or more ahead of Hancocks. When the ball came out of defense to Hancocks, he was able to chip it accurately to Broadbent who was frequently clear on his own. This stratagem, designed to make the fullest use of the best qualities of both players, was also extremely successful, for the full-back marking Hancocks was caught between two men and played out of the game. As we were working largely to the law of averages, determined to ensure that the ball spent a far larger proportion of each match in front of the opposition goal than in front of ours, it is a logical sequel that, once we had put the ball into the other team's danger area, we could not afford to allow them to obtain possession of it without a fight. So I needed forwards who could challenge and tackle and struggle for every loose ball. In 1950, I was fortunate in that I had an ideal player for this type of game in Roy Swinbourne, the young Yorkshireman who came to Molineux from Wath Wanderers, the nursery team of Wolves which is run by Mark Crook, one of our old players. Tall and strong, Swinbourne could gain possession of the ball on the ground and, in the air, he could beat most defenders. As he learned, and removed the rough edges from his game, he developed into a first-class centre-forward for Wolves and was just coming to the peak of his career when he injured a knee in the last minute of a game at Preston. This unfortunate injury happened early in the 1955-6 season and, although he tried for nearly two years to find his old speed, Swinbourne never recovered from that accident and now he has to be content to referee local games in Wolverhampton. Although the game may have found a first-rate official, football lost a potentially great centre-forward. At the time of Swinbourne's accident, I knew that Wolves would find it very difficult to replace a key man in the tactical plan. I did not realize that, three years later, as we played in the European Cup for the first time, I would still be without an adequate substitute. For Swinbourne was one of the few powerful forwards in the modern game who could fight and tackle for every ball in the manner of Peter Doherty, Raich Carter or Jimmy Hagan. (8) Ron Flowers, For Wolves and England (1962) Mr. Cullis, as our chief, and the mainspring on the playing side, possesses a tenacity and drive few other men can equal. As I remarked earlier, I do not always agree with him, but there is no disputing he has in every way proved himself to be one of the most successful managers in modern football. The Stanley Cullis approach to the problems of modern football always makes interesting hearing, and reading, for he thinks most seriously about all aspects of the game and his reactions often intrigue me. Many managers, when a team is passing through a lean spell, would prefer to sit down and talk over the current problems with his players. But not our chief. As a former player of distinction, he realizes that a player knows when he is playing badly and must be worried. He never adds to our worries at such a time by large-scale inquests, and I for one deeply appreciate this approach. Our manager, on the other hand, has very thorough and searching tactical talks when we're doing well, which over the past ten years means we've had plenty of discussions. One of the great qualities of Stanley Cullis as a manager is that he knows what he wants. The "boss" likes to hear our ideas, and encourages us to air our views. But as our manager he'll tell us when he disagrees, and straight from the shoulder say what he requires from us all. On a Saturday, if we have not had a team talk, he will always come to the dressing-room before the match to have a word with certain players to discuss the men opposing them. Mr. Cullis's advice is always on target. During the course of a season our manager spends as much time as possible watching the teams we will oppose. He makes a mental note of the players we will be meeting and he has what I can only term a photographic mind. If Stanley Cullis tells you that your opponent has certain strong qualities, and weaknesses, you can be certain he is giving you the right advice. In setting out to achieve success on the field for Wolverhampton Wanderers our manager never sets out to copy the tactics of any other club. He has his own individual approach to the game. It is an outlook that has brought with it success to his teams, and, briefly, I think his basic plan is to split the field into three parts. One third of the pitch contains our goalmouth; one third is mid-field; the final third is our opponents' section of the field. The Wolves plan is a simple one to follow. The idea is to get the ball as often as possible into the third of the field defended by our opponents, for it is from this position the Wolves score their goals. (9) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960) Further modifications to the tactical plan-although fundamentals remained unchanged-were necessary to cope not only with the retirement of Swinbourne but with the departure of Hancocks too. The little winger, who was no youngster, left us in 1957 to become player-manager of Wellington Town, the Cheshire League side. My decision to release him was not entirely popular in Wolverhampton but I felt that it was necessary to prepare for the future. Hancocks could not have played in the First Division for very much longer and I had no player of similar style and ability to take over from him. So, in March 1956, I paid the biggest fee in Wolves' history-the newspapers quoted it as £25,000 - for Harry Hooper, the young West Ham United outside-right, a winger who I thought had all the qualities to succeed Hancocks. I had my eyes on Hooper for a long while before I read in the papers one morning that Tottenham Hotspur were keen to sign him. I went quickly down to London and, although the transfer deadline for that season had gone, I managed to complete the deal. Like Hancocks, Hooper was fast, direct, able to play on either wing and was both accurate and powerful in his use of the ball with either foot. In short, he was an ideal winger. But, as Burns wrote, the best-laid plans of mice and men "gang aft agley". The Scottish poet might have been writing especially for football managers. At Molineux, Hooper found it extremely difficult to adapt himself to our style. He played several outstanding games for us but there was no doubt that he did not carry out our tactical principles to the extent I considered was essential. Two seasons later, Birmingham City made a big offer for the former West Ham winger and, as Norman Deeley had made considerable progress, I decided to release Hooper to St Andrews. (10) Stan Cullis, All For the Wolves (1960) As I have said in earlier chapters, no club can hope to succeed in the tough competition of modern football unless the players combine in their personality three principal factors. They must have tremendous team-spirit, must be superbly fit and must use the correct football tactics on the field. The object of the training curriculum is to ensure not only that Wolves are faster and stronger if possible than each team they meet in the League, but that they also have sufficient fitness to employ to the best advantage the team-spirit and the tactics which we try to inculcate into them. Those tactics demand that Wolves play at a tempo which is beyond the capacity of the other side. Because our opponents are forced to play at a pace which is foreign to them, they are likely to make far more mistakes than would be the case if they strolled along at their own sweet rate. Around 1955 there were quite a number of teams, even in the First Division, who were not trained to a pitch that I would describe as adequate. Now, so far as stamina or speed are concerned, Wolves have lost a little of the advantage which used to be theirs. The fundamentals of our tactical approach to football at Molineux demand that the ball is moved from one end of the field to the other in the quickest possible time. This involves rapid tackling by every player so that we obtain possession of the ball before the other side has it under control. We cannot send it back into their defensive area until we have possession. Our players are consequently required to make short sprints of twenty or thirty yards more often and more quickly than most. It is essential that they are able to make those sprints without any effort, even at the very end of a hard game, for, in their ability to do so, lies the difference between victory and defeat. My war-time experiences in the Army taught me, as they taught many people, that proper training can cause the abnormal achievement to become a normal one. Thus, the man who could not walk a mile with a shopping-basket in 1939 was often marching ten miles at a smart pace with a hefty load on his back by 1943. At Molineux, we strive to make the abnormal an everyday achievement. I tell my players that they must train until it hurts because it makes them better players on Saturday. If they are taught to run faster and farther in training than is strictly necessary in matches, they will play those matches more easily and with greater confidence. The main training program is divided into six parts, each with its own objective, and, as the season lasts for approximately thirty-six weeks, we allow the equivalent of six weeks for each section. The program aims to co-ordinate these six factors into every player: i. Stamina. ii. Speed. iii. Agility which is the co-ordination of mind and muscle. iv. The scientific application of athletics to football. v. The conservation of energy. vi. The utilization of ground coverage. Stamina is a most important point for, if we are to use tactics designed to force the other side to play at a pace to which they are not accustomed, we naturally need to have a greater reserve of strength than the opposition. Again, if our players are faster than the other side, we must also have the stamina to maintain that advantage until the end of the game. The foundations of our stamina are laid in the weeks before the start of the season. The work which is done in the four or five weeks of late July and early August pays dividends in the winter months of November, December and January when training is more difficult. In these early weeks, we build up quickly to regular six-mile runs on the roads outside Wolverhampton. Gradually, too, we step up the pace of those runs until the players are covering the distance in little over half an hour. The value I placed on this form of training was responsible for the arrival of Frank Morris at Molineux. In all kinds of work, people respond to leadership and neither Joe Gardiner nor myself was fit enough to lead the players regularly on six-mile runs. Nor can leaders lead on a bicycle. So Morris, a former A.A.A. champion, an international runner and an athletics coach who has always been a keen Wolves' supporter, volunteered his services. Now he is the man who heads the file on those long jaunts and he enjoys it too! By the time the season opens, the players are as hard as nails, able to play at a cracking pace not only for ninety minutes but for a hundred and twenty minutes if necessary. Once the requisite level of stamina is achieved, it can be maintained without the need for long and regular work on the roads. Although we sometimes send the players out for a long run, we are generally able to keep to the right tenor by use of careful exercises with weights and perhaps a three-mile run once a week. Weight-training, which involves a circuit of eight specialized exercises, is done in the dressing-rooms and gymnasium. Wolves, I believe, were one of the first football clubs to make extensive use of weight-training. Now most clubs and, in fact, most sports place considerable confidence in weights to build up both stamina and speed. The hour which our players spend at Molineux in this form of training each week is most important. If stamina, however, is the basis of proper training, equal emphasis must be placed on speed both of action and thought, on skill and conservation of energy. The training programme at Molineux is devised to take care of all these points. If the fixture-list does not include a match in mid-week, the Wolves' professionals work for around nine and a half hours each week. The general schedule allows only Sunday as a complete day free from training. The rest of a typical weekly program reads: Monday: Light ball-work for 100 minutes in the morning. Tuesday: A three-mile run, sprinting, hurdling and agility training for 100 minutes in the morning. Weight-training and ball-work for a similar spell in the afternoon. Wednesday: A morning practice match or training in football boots for two hours in the morning. Thursday: Sprinting and running, ball-work in the morning. Positional and individual coaching in the afternoon. Friday: Sprinting, exercises and light ball-work for an hour. The ability to run fast on the field, with or without the ball, is of no real value to a player unless his brain is moving at an equal speed. "He'd run out of the ground if they opened the gates," is a phrase often heard on the terraces when a flying winger has lost the ball or held it until he is forced out of play. That sort of man does not win Championships, so a considerable part of the training time at Molineux is designed to co-ordinate mind and muscle. The athletics training is arranged in such a way that a player has to move quickly and think quickly at the same time. |

| +-+ BACK TO TOP +-+ | |