| |

|

THAT IS NOT A FOUL REF!

Foul recognition...

The science of decision-making processes among outstanding referees

WineCape's Referee Blog

IMHO – a South African Football Referee's View

|

With the World Cup almost upon us in South Africa (kick-off 11 June

2010), I am getting numerous phone calls from people asking for football

advice and general information on the Laws of the Game. The FIFAWorld

Cup, being the biggest sporting event on the planet, and being an

occasion as much as a football extravaganza at the highest level, have

inspired some non-football watchers and friends of mine to apply and get

World Cup tickets. (They seem to have better luck getting tickets then I

do!

) Callers and friends are of the opinion that they are not going to miss

this historical event being held for the first time on African soil, a

lifetime experience to be enjoyed and savored, even though some are not

regular watchers of football, or soccer as its called here.

) Callers and friends are of the opinion that they are not going to miss

this historical event being held for the first time on African soil, a

lifetime experience to be enjoyed and savored, even though some are not

regular watchers of football, or soccer as its called here.

I was recently invited to a two hour radio talk on the Laws of the Game

and the most common questions asked were how many fouls are there and

when/how do you as a referee decide when it is a foul or not? The answer

to the first part is easy: ten fouls as described in Law 12, but getting

to grips on the how and when to identify fouls consistently and

correctly, given Law 12’s instructions, can take referees years to

master if they want to become top class officials.

Referee decision-making is a fascinating and complex area. Each referee

will deal with decision-making in their own individual way, and will

often rely on a combination of intuition, experience and their knowledge

of the Laws. Certain referees are capable of making instant decisions,

whilst others rely more on having the infringement played over in their

mind before calling a foul, thus giving them time to appraise all of the

relevant information and factors.

|

Experienced referees rely greatly on their “gut feeling and

instinct,” and their own automatic conscious or unconscious

reactions when making judgment calls. Decisions based on

well-developed instincts are often proven to be correct.

Trusting your own instinct will serve you well as a referee,

more often then not. That is to say, if your instinct is well

developed! There is no substitute for experience, as instinct -

that “gut feel” – is acquired over time and practice. The

essence of outstanding referees are their ability to make

decisions instinctively within the simple framework of the 17

Laws of the Game. |

Making correct decisions are complicated by a number of

factors:

(1) a sine qua non is knowledge of the 17 Laws,

(2) the speed of play,

(3) the distance between the incident and the referee – also known as

“closeness” to play;

(4) his fitness;

(5) whether there are players obstructing the Referees' line of sight

(viewing angle);

(6) whether assistant referees are available or not;

(7) the referee’s technical aptitude or natural ability;

(8) the referee’s eyesight, including his peripheral awareness.

All the above play a role in various degrees. With regard to closeness

to play – given the saying “presence lends authority” – the following

footnote: In the 1986 World Cup, detailed referee analysis showed that

decision errors were more likely to be made when referees were too close

to the incident. When the officials got it right, they were, on average,

17 meters away from the action. The average distance in the case of

decision errors were 12 meters. Research shows the optimum distance for

correct decision making to be roughly 20 meters from incidents.

An astute referee understands that there will be many decision-making

situations that do not neatly fit the answers provided by the Laws. The

ability to interpret the Law is therefore an important asset. It is not

only an understanding of the 17 Laws that makes a good referee; it is

also his interpretation or decision-making ability, in conjunction with

common sense, self-assessment, managing the temperature of the game,

self-analysis and adhering to the overarching principles of “Spirit of

the Game” and “Fair Play.”

Research shows that in football matches referees are expected to make

many decisions (observable and unobservable) during 90 minutes. Analysis

in the Euro 2000 Final tournament suggests that an international match

official make 137 observable interventions on average

(the range is 104-162 decisions) during a game, including awarding

free-kicks, penalties, corners, throw-ins and halting play for serious

injury. 64% of these decisions were based on direct communication with

his assistants and/or 4th official. (Helsen & Bultynck, 2004).

Roughly a quarter of those decisions relate to possible interventions

pertaining to fouls and misconduct (Law 12). Each decision must be

calculated in the smallest fraction of time, usually within a second or

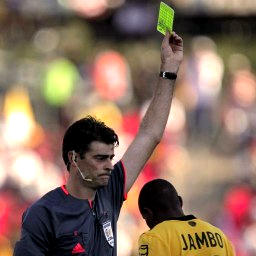

two. The possible responses of a referee who identified a foul vary from

(a) indirect free kick, (b) direct

free/penalty kick in combination with a yellow card (caution) or a red

card (sending off). All of these sanctions have clearly an impact on the

course of a game. Empirical observations done indicate that on average

20% of referees’ decisions are wrong when it comes to identifying fouls

and misconduct.

According to the Max Planck Research Institute, learning to make

accurate referee decisions inter alia require repeated exposure to

infringement incidents (via video training material) with corresponding

feedback. Hardly a surprise, given the old adage “practice makes

perfect.”

FIFA published a starter document in 2002 to aid match officials in foul

recognition, i.e. when fouls are being considered careless

(a free kick only), reckless (free kick +

caution) or being committed with excessive force (free

kick + expulsion).

The definitions of careless, reckless and excessive force in football

vernacular are stipulated as: A careless tackle is defined as a player

showing a lack of attention or consideration when making his/her

challenge without precaution. A reckless tackle is a player that made an

action with complete disregard for, danger to, or consequence for, his

opponent. Using excessive force means that the player has far exceeded

the necessary use of force and is in danger of injuring his opponent.

Bear in mind the definition of a foul. It’s a specified

unfair action within the ambit of offenses – as defined in Law 12 – that

is committed:

1. Against an opponent (not a team mate);

2. While the ball is in play;

3. On the field of play

All the above criteria must be present before the specific unfair action

can be classified as a foul. Further, fouls are only committed against

opponents. If a player hits his own team mate, that action is classified

as misconduct, not a foul. The restart will be an indirect free kick to

the opponents, and not a direct free kick as the case where 2 opponents

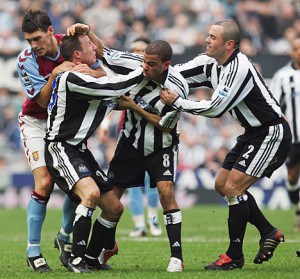

were slugging it out against one another. Does this happen in modern pro

football? Oh yes they do… It seems the English league is never short of

football examples to instruct referees. Have a look here …

Lee Bowyer vs Kieron Dyer,

fighting one another.

Newcastle (0) vs. Aston Villa (3), April 2005. |

The Football Association fined Lee Bowyer £30,000 and

imposed an additional three-game ban, and his club Newcastle

fined him a further six weeks’ wages (+/-£250,000); Dyer was not

fined as Bowyer was perceived to have thrown the first punch. In

addition, Bowyer was charged by Northumbria Police in connection

with the brawl with offences under section 4 of the Public Order

Act. He pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of using threatening

behavior, paying a further £1,600. Newcastle ended the match

with 8 players as Steven Taylor had earlier been sent off for a

second caution able offence! |

But I digress...

Indicators that referees, according to FIFA, should use to identify

specific challenges as being executed in either in a careless manner, a

reckless manner or using extreme/excessive force – sometimes referred to

as brutality – are below.

1.

Judging the body actions of the tackler by noting the point of contact –

Referees are instructed not to judge intent, but only action. The

reasoning is that we are not able to conclusively interpret player

intentions, therefore we are limited to judging their physical body

actions (flaying arms, trailing leg, raised boot with studs showing,

two- or one-footed lunges off the ground etc.);

2.

Noting the speed of the approach by the tackler on the player about to

be tackled;

3.

Looking for any signs of aggression shown by the tackler;

4.

Recognizing any signs of violence associated with the tackle;

5.

Position of the tackler: is the tackle from the back, or the side, or

from the front;

6.

What opportunity the tackler has to play the ball fairly – getting the

ball first does not necessarily imply no foul was committed if the

tackler uses speed and/or aggression disproportionately. (A seemingly

difficult concept for some pro players to accept!)

7.

Taking into account the atmosphere of the game, or the feel of the game.

FIFA has since clarified that the position of the tackler is about

fairness and player safety; that is, whether the player about to be

tackled is aware of the opponent’s location. (Do note: a tackle from any

direction which the referee judge to be careless, reckless or using

excessive force should be punished accordingly).

Being aware of match atmosphere reminds referees to be alert to the type

of match they are controlling, that is whether it is a bad tempered,

fouling affair or a skilled sporting contest. If it is a nasty contest

referees should be very alert and suspicious when a player runs hard at

an opponent. This is a good example of being pro-active in their

control, as they should be.

Julian Carosi identifies 3 types of decision-making

processes referees are faced with.

- 1. Statutory decisions:

These are objective decisions – i.e. they are either right or they are

wrong according to the Laws of the Game.

- 1. Statutory decisions:

These are objective decisions – i.e. they are either right or they are

wrong according to the Laws of the Game.

- 2. Interpretational decisions:

How the Referee interprets the Laws. A subjective decision, i.e. reading

between the lines

- 2. Interpretational decisions:

How the Referee interprets the Laws. A subjective decision, i.e. reading

between the lines

- 3. Impossible decisions:

The ability to quickly and confidently make a ‘best guess’ or ‘default’

or ‘benefit-of-the-doubt’ or an ‘equal’ decision (such as a drop ball).

- 3. Impossible decisions:

The ability to quickly and confidently make a ‘best guess’ or ‘default’

or ‘benefit-of-the-doubt’ or an ‘equal’ decision (such as a drop ball).

Note that in order to correctly INTERPRET the Law, you have to KNOW the

Law. Thus (1) above is a pre-requisite for (2).

Making statutory decisions depends greatly on a Referee’s knowledge of

the Laws and his ability to keep abreast with Law changes, –

developments and – amendments during his career. Statutory decisions are

the easiest to make – because the referee knows (or should know!)

beforehand, exactly which Law is applicable for punishments or

conclusions or decisions he is basing his decision on. An example of a

common statutory Law error made by new referees, is the failure to

understand that when a free kick is taken inside the penalty area by the

defending team, the ball has to travel outside of the penalty area

before it comes into play, and before another player can touch it.

Learning the Laws by heart, and passing the initial referees’ exam is

the easy part. The difficult part is being able to apply the Laws, being

able to interpret the Laws in such a way that the players get the

maximum enjoyment out of their game. The key to this is the ability of a

referee not to be a complete dictator, but to recognize and react to the

ambiance and feel of each game, and to be able to adjust his levels of

control throughout the 90 minutes. Decision-making is key to this

requirement – along with ability to bend and flex the rules in such a

way that it promotes the Spirit of the Laws by using what is generally

known as Law 18 – Common Sense.

A few examples of where good interpretation of the Laws and quick

confident decision-making are required for a referee to retain his

credibility as an official: (a) Was the handball deliberate? (b) Should

the player be cautioned or will a stern public warning suffice? (c) Can

a referee drop the ball to the goalkeeper without any other players

being involved? (d) Is the attacking player standing in an offside

position, actively involved with play or not? Common sense and Law

interpretation used fairly and correctly, separates the good referees

from the not-so-good officials.

The third part of the decision-making process is the impossible

decisions. There will be many occasions in each game, when it will be

impossible for the referee to make a correct decision: (a) Has the ball

crossed the goal line marginally with the referee (or his assistant)

many yards away and not 100% sure? (b) Two opponents are competing for

possession of the ball very near to the goal line. The ball

simultaneously hits the shins of both players, and travels completely

over the goal line. Both teams are equally entitled to the decision. But

what should the referee award – a goal kick or a corner kick?

The decisions mentioned in the above examples seem to be the most

difficult ones to make, but with a little preparation they are,

according to Julian Carosi, the easiest decisions to make if you take

note of the following criteria:

- Be ready by anticipating problems

- Be ready by anticipating problems

- Get as near as you can to active play

- Get as near as you can to active play

- Be firm

- Be firm

- Be quick

- Be quick

- Be positive

- Be positive

- Do not waver or hesitate

- Do not waver or hesitate

- Stand erect when delivering your decision

- Stand erect when delivering your decision

- The more difficult the decision – the more you will need to “sell” it

- The more difficult the decision – the more you will need to “sell” it

- Look players in the eye confidently

- Look players in the eye confidently

- Provide clear and quickly delivered signals

- Provide clear and quickly delivered signals

- Do not be influenced by others once you have decided what to do

- Do not be influenced by others once you have decided what to do

- Your decision counts and nobody else’s. So be ready to deal with the

inevitable ensuing dissent

- Your decision counts and nobody else’s. So be ready to deal with the

inevitable ensuing dissent

- Look at the reaction and the body-language of the players, i.e. don’t

(out of hand) dismiss passionate shouts by a team for a decision in

their favor

- Look at the reaction and the body-language of the players, i.e. don’t

(out of hand) dismiss passionate shouts by a team for a decision in

their favor

- Don’t worry too much if everybody else thinks you are wrong – for now,

you’re right!

- Don’t worry too much if everybody else thinks you are wrong – for now,

you’re right!

- And finally – maintain 100% concentration at all times.

- And finally – maintain 100% concentration at all times.

Note: In situations where the referee has realized he

made a genuine mistake, he can change his decision, according to the

Laws of the Games, as long as play has not restarted or he has not blown

for the end of the match. Players and coaches are usually receptive to

an honest mistake being rectified – the referee just needs to admit that

he was wrong in the first place.

Embed default decision-making scenarios in your mind. Some standard

examples of these types of decisions are shown below. If you can adopt

these, it will make your impossible decision-making very easy and

automatic. The trick is to make life as easy as possible for yourself by

lessening any potential trouble ensuing because of your decision.

If you need to make a decision but are not sure which way to

go:

- Award throw-ins to the defending team.

- Award throw-ins to the defending team.

- Award a goal kick rather than a corner kick.

- Award a goal kick rather than a corner kick.

- If you are unsure whether an attacking player is offside or not – give

the benefit of doubt to the attacking team.

- If you are unsure whether an attacking player is offside or not – give

the benefit of doubt to the attacking team.

- If you are unsure of whether the ball was last played by defender or

an attacking player when deciding offside, give the benefit of doubt to

the attacking team.

- If you are unsure of whether the ball was last played by defender or

an attacking player when deciding offside, give the benefit of doubt to

the attacking team.

- Award free kicks to the defending team – especially during corner

kicks.

- Award free kicks to the defending team – especially during corner

kicks.

- Is it a direct free kick just outside the penalty area or is it a

penalty kick? Award a direct free kick.

- Is it a direct free kick just outside the penalty area or is it a

penalty kick? Award a direct free kick.

- Is it a penalty or not? No penalty.

- Is it a penalty or not? No penalty.

- So called “Orange card” tackles – the foul is a caution/yellow (i.e.

reckless challenge), but it borders on red (i.e. serious foul play).

What to do? Sent off! Err on the side of an expulsion, as per Fifa’s

latest mantra. Coaches will rather accept a “harsh” red then a “weak”

yellow.

- So called “Orange card” tackles – the foul is a caution/yellow (i.e.

reckless challenge), but it borders on red (i.e. serious foul play).

What to do? Sent off! Err on the side of an expulsion, as per Fifa’s

latest mantra. Coaches will rather accept a “harsh” red then a “weak”

yellow.

- Was the handball deliberate or not? Not deliberate. (See criteria

below)

- Was the handball deliberate or not? Not deliberate. (See criteria

below)

- Has a goal been definitely scored or not? No goal.

- Has a goal been definitely scored or not? No goal.

FIFA also defines the criteria to help referees assess the

deliberateness of handball. Handball is defined as the whole arm,

stretching from the outer shoulder to the fingertips. Handball is not an

offense. It has to be deliberate. Factors that could help in classifying

handball as deliberate and thus an offense punishable with a direct free

kick are:

- Distance of the kicker and the player;

- Distance of the kicker and the player;

- The reaction time the player has, if any, to move his arm away

(unexpected ball);

- The reaction time the player has, if any, to move his arm away

(unexpected ball);

- Original hand/arm position of the player;

- Original hand/arm position of the player;

- Whether the ball moved towards the hand/arm (ball kicked onto the arm)

versus a hand/arm moving towards the ball.

- Whether the ball moved towards the hand/arm (ball kicked onto the arm)

versus a hand/arm moving towards the ball.

If the above factors do not convince the referee to punish the

infringement, he is instructed to refrain from calling handball.

“Deliberate” means that the player could have avoided the touch with his

arm/hand but chose not to. Moving your hands or arms instinctively to

protect the body when suddenly faced with a fast, unexpected approaching

ball does not constitute deliberate contact unless there is subsequent

action to direct the ball once contact is made. Likewise, placing the

hands or arms to protect the body at a free kick or similar restart is

not likely to produce an infringement unless there is subsequent action

to direct or control the ball. The fact that a player may benefit from

the ball contacting his hand does not transform the otherwise accidental

event into an infringement.

“That is NOT a foul ref!” or “Are

you booking me for that?” My usual retort on-field is to

ask said player what Law has been transgressed or not, if he’s then so

certain of his case? Silence is mostly the reply. If you want to

interpret the Law correctly, you have to know the Law first.

Paradoxically, given that they ply their trade in professional football,

most professional players, coaches and football commentators – it seems

ex-pro players going into journalistic careers are not exempt either -

in South Africa are clueless when it comes to the first basic step; real

knowledge of the 17 Laws of the Game, never mind interpreting the Laws

correctly according to FIFA directives.

| The hardest aspect of being a English Premier League

Referee? 62% of the Referees revealed that they generally

thought the uneducated, personal, biased and unfair scrutiny

they were subjected to by the media was a burden on their

officiating role in the Premier League. – Mason &

Lovell 2000 |

A SAFA Referee course was held some years ago for football commentators.

Most did not bother to pitch up. Yet, they are the so-called pundits

where millions believe every word or opinion on the Laws they utter on

live television and print. That’s not to say commentators are always

incorrect and Referees don’t make any mistakes; I’m willing to bet my

FIFA toss coin that referees will have 50% less “trouble” if these

football “pundits” really know the Laws and interpretations as

they should be applied according to FIFA, as per the

well-informed SABC television commentator Duane Dell’Orca (and a very

small minority) that has shown consistently and admirably their

knowledge on the Laws of the Game over the past few seasons.

I have lost count the amount of silly yellow cards I issued to players

this season because they refuse to respect the 10-yard distance at free

kicks in the professional league. In this regard the Law allow referees

not much leeway or discretion. If a player refuses to move back -

usually after I warn them first – they must be cautioned. Tell that to

players, coaches and commentators complaining that referees should use

their discretion in this instance. There is no interpretation, no

discretion, no discussion. It’s

black … or white.

|